Opera

everywhere

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

In chapter 4, Artemis Ignatidou, the author of this text, urges us to “open boxes” –, those that found their way onto the operatic stage and those in which opera itself sneaked into. Through this exploration we will understand why opera is actually everywhere! Moreover, artist Petros Touloudis reveals his anime-influenced sources of inspiration for the costumes of the production Offenbach’s La belle Hélène.

Artist and set-designer Petros Touloudis discusses his anime-influenced sources of inspiration for the costumes of Offenbach’s La belle Hélène.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / OPERA OUT OF ITS ‘BOX’

Have you ever tried to make a puppy sit still inside a box? The little dog will soon wag its tail, yap excitedly, sniff around, and then jump to the next box to play with its friends. Believe me when I tell you that something similar happens with the arts but with less tail wagging.

You see, if you think of opera simply as ‘classical’ music with song and dance, you will soon see it leap out of this ‘box’ and mix with many more genres of music than you could even imagine!

Until now we saw how opera was first performed to entertain aristocrats and their aristocrat friends in a serious Italian manner and then it ‘leaped out’ into public theatres and it became all sorts of things: it became French, it became German, it became Greek, it became digital, and we didn’t even get to see how it became Turkish, Chinese, or Argentinean. Sometimes it was funny and sometimes it was sad, sometimes it was tiny and sometimes way too long. So now it’s time we saw some examples of other genres of music that ‘leaped into’ the box where opera was sitting, how they played together, and what new songs they yapped together.

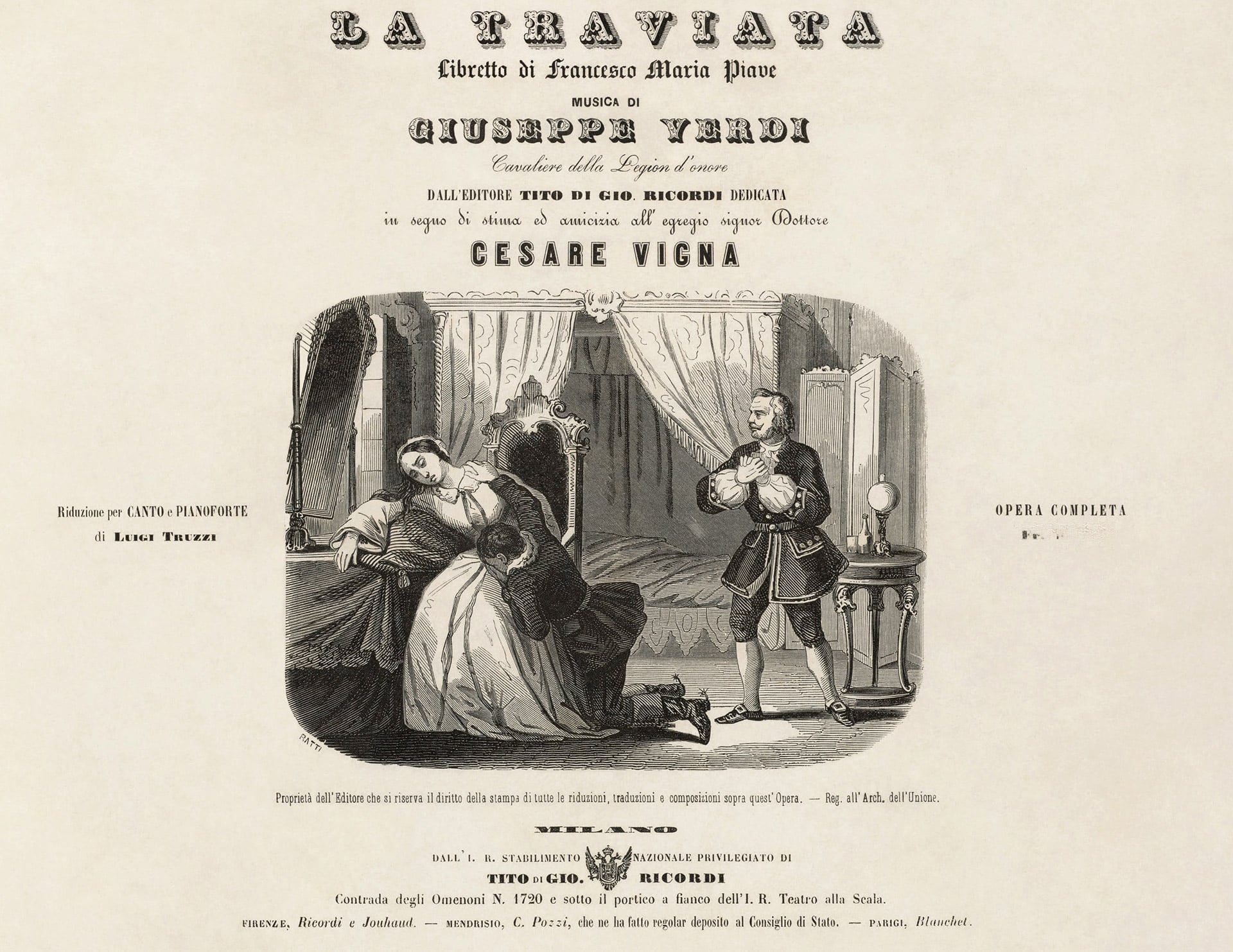

Title page of the vocal score for Giuseppe Verdi’s popular opera La Traviata, [Harvard Library], Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Our story here begins in the United States in the early 1900s, when music publishers began selling edited versions of popular operatic arias for the piano – that are called ‘arrangements’ or ‘vocal scores’. In this small but significant way, from aristocratic courts and expensive theatres, opera suddenly found its way into the everyday life of people who wished to enjoy, sing and play it in their living room.33L. Hamberlin 2011, Tin Pan Opera. Operatic novelty songs in the ragtime era, σ. 3-5. At the same time, similarly to the likes of Mozart who used traditional and popular music in their compositions, musicians from other genres of music experimented with inserting tunes from the operatic repertory into their own musical style. In this any many other ways that we will see in this section, ever increasing numbers of people came to contact with aspects of opera they could immediately recognise as part of this musical tradition or enjoy without ever knowing they were secretly dancing to opera.

CHAPTER 3 / THE MUSICAL

I am certain that you already know a lot about the first box we will open to see how much opera we will find inside. It is a box full of instrumental music, theatre, song, and dance that is, nevertheless, not exactly opera.

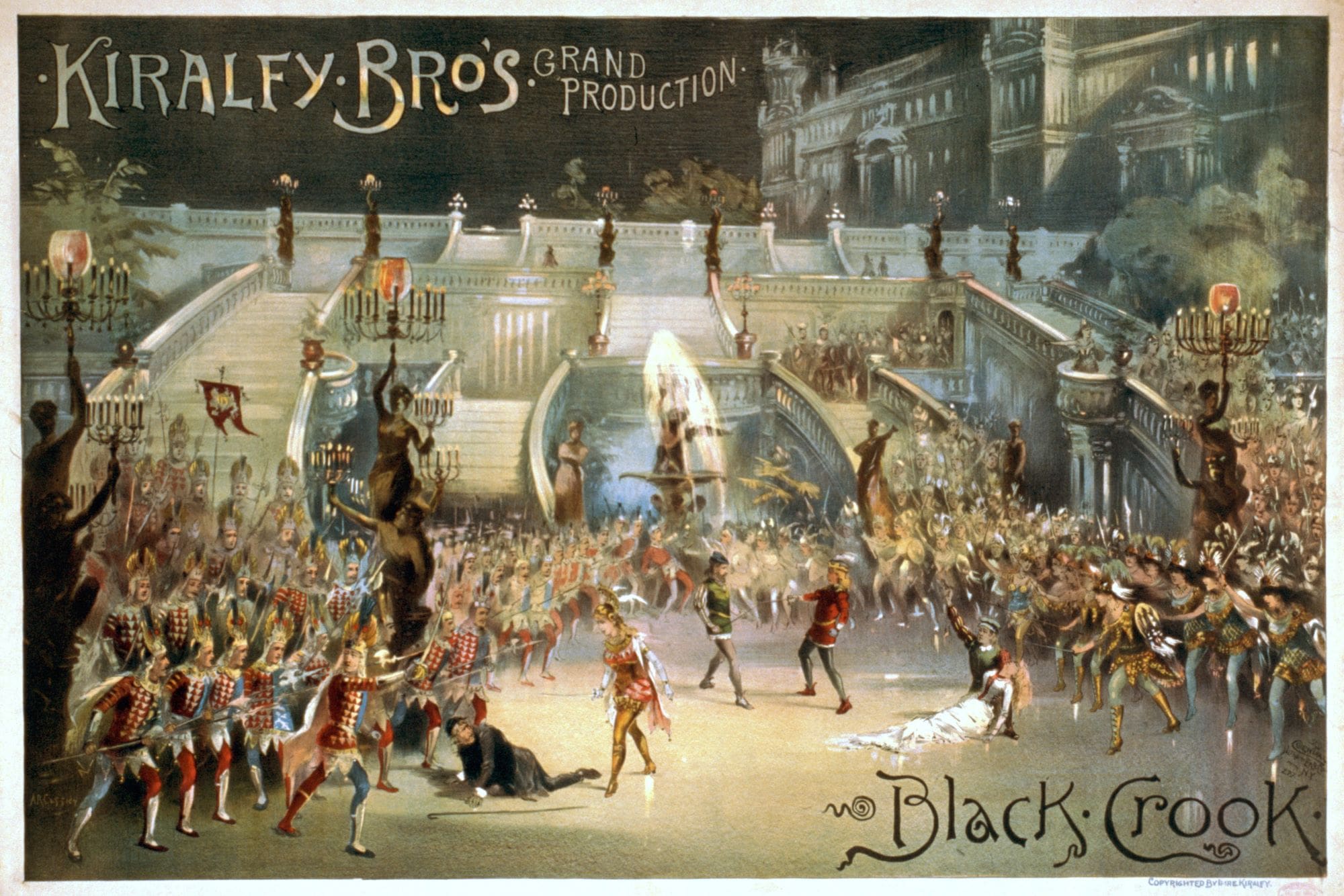

The widely popular genre of the ‘musical’, which we now enjoy in theatres and cinemas, first appeared with the performance of the musical comedy ‘The black crook’ in 1866 New York. But wait a second, I can hear you protesting, if an art consists of instrumental music, song, theatre, and dance then surely it must be opera or operetta! And your objections are entirely justified. But let’s try it this way: If we think of operetta as the musical’s grandpa and opera as operetta’s older sister then we have a nice little group of related genres that are similar enough to belong to the same ‘family’ but are also distinguishable from each other. So what are the most important of these differences?

In opera singers deliver their text in the ‘recitativo’ style between the arias. In operetta and musical the text is not ‘sung’ in the recitativo style but performers speak like they would in theatre in-between their songs. Another important distinction is that performers in musicals sing their songs in the technique we find in all other genres of music, unlike opera where singers use the special ‘operatic technique’ that gives their voice a specific texture and colour. Dance is represented equally with the other arts in musicals and the singers-actors usually participate in the choreographies. On the contrary, when dance is included in opera it is performed by dancers. Therefore, if we sum up all these differences we will see that musical is a form of entertainment often performed by actors with advanced training in singing and dance, who perform popular songs. They do not use the operatic singing technique, the plot is advanced through spoken word, and dance is as important an element as the rest of the art-forms on stage.

Poster for the famous musical The Black Crook

Other beloved musicals include: The Phantom of the Opera (by Gaston Leroux, music by Andrew Lloyd Webber), Les Miserables (by Victor Hugo, music by Claude-Michel Schönberg). Popular musicals for the TV and cinema include: The producers (by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan, music by Glen Kelly and Mel Brooks) as well as Chicago [screenplay by Bill Condon, music by John Kander, Danny Elfman, and Steve Bartek].

Excerpt from the musical Once, produced by the Greek National Opera. [Playwright Enda Walsh, music and lyrics: Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová, direction: Akilas Karazisis, starring: Marina Satti and Apostolis Psychramis]

CHAPTER 4 / FROM JAZZ TO POP AND FROM ROCK TO HIP HOP

Connecting opera to musical was fairly easy since, if anything else, most of us already suspected that these two genres were somehow related. But did you know that legendary jazz, rock, and pop musicians have experimented with musical ideas borrowed from the opera in order to see how they would sound in their own genres?

The famous American trumpeter Louis Armstrong, for example, who experimented with opera throughout his career, left musical references to Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Rigoletto in his pieces New Orleans Stomp and Dina. Moreover, in his pieces Tiger Rag and New Tiger Rag he drew inspiration from Ruggero Leoncavallo’s opera Pagliacci. And if you are looking for a particularly amusing example of this musical exchange between the genres, look up the song Mack the Knife, from Kurt Weil’s The Threepenny Opera. Jazz and pop music stars such as Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra and Boby Darin have performed this otherwise dark song with great success. How did these adaptations change the style of the original song? What other performances can you discover?

![Among the various singers who have performed Mack the Knife from Kurt Weil’s Threepenny opera [Die Dreigroschenoper] we find the widely beloved Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996)](https://operabox.nationalopera.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/4.4_Ella_Fitzgerald_Gottlieb_02871_RD-min-969x1024.jpg)

Among the various singers who have performed Mack the Knife from Kurt Weil’s Threepenny opera [Die Dreigroschenoper] we find the widely beloved Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996), photo by William P. Gottlieb, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

As for those of you with a preference for loud music, you must already know that in the 1960’s and the 1970’s important British bands, such as ‘The Who’, ‘Nirvana’ and ‘Pink Floyd’, composed music that was later termed ‘rock opera’. That is, rock music albums whose independent tracks tell a continuous story and contribute in this way to the development of a plot with individual ‘characters’, expressed in the musical idiom of rock. The first albums to present this style were S. F Sorrow (1968) by ‘The Pretty Things’ and Tommy (1969) by ‘The Who’. In 1979 the band ‘Pink Floyd’ released the album The Wall, while a little earlier, in 1975, a ‘zong opera’ on the myth of Orpheus and Euridice became the first Soviet-Russian rock opera.

‘The Who’, one of the rock bands to compose music for the genre later termed ‘rock opera, in concert in Hamburg in 1972

In the USA during the same period rock operas on Christian themes flourished, with Jesus Christ Superstar by British composer Andrew Loyd Weber opening on Broadway in 1971 and turning into an instant success both in the US as well as in Great Britain. In 2004 the BBC, Britain’s public broadcaster, aired the parody- opera AD/BC, a humouristic take on this 1970’s American craze. As you can see, rock opera has not only been popular entertainment for many decades but it has been so popular as to warrant the production of a comedy-opera on the theme of rock opera.

And if you are indeed into loud music and find the idea of rock opera appealing, yet you do not enjoy rock music, you could always test if a hip- hop opera is more to your liking. Similarly to the idea of rock opera, the experimental group ‘Clipping’ presented their inter-galactic adventure Splendor & Misery, which they described as a ‘hip-hop opera’. In a similar fashion with rock opera, the group maintained the story-telling aspect of traditional opera to tell a musical story in their own style.

Do you know other rock operas and which one is your favourite?

Excerpt from LIVER by Efthymis Filippou. Notice the musical reference to the famous rock song Riders on the Storm by The Doors. A co-production between the Alternative Stage of the Greek national Opera and ‘Ictus’ ensemble of contemporary music.

CHAPTER 5 / OPERATIC SONG

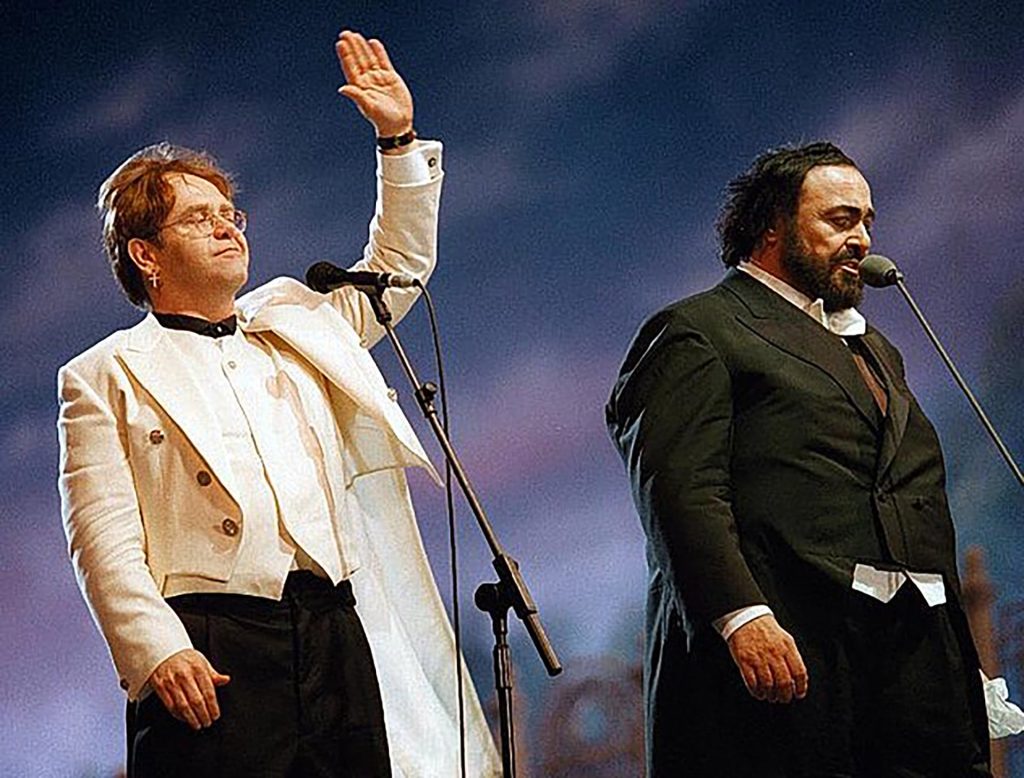

From 1980 onwards, famous opera singers started presenting popular arias from the operatic canon but without the staging or the costumes, in shows that aspired to reach broader audiences.

Groups like ‘The Three Tenors’, featuring the tenors Placido Domingo, Jose Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti, became particularly popular in the 1990s. Similarly you may remember operatic singers representing their countries in the Eurovision song contest, bringing opera into the house of audiences who would not otherwise choose opera for their entertainment.

The English singer, songwriter, and pianist, Elton John, with the Italian tenor Lucian Pavarottin during the “Pavarotti & Friends” concert in the Italian city of Modena in 1996, ANSA, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Among the most famous collaborations of that period was certainly the one between Freddie Mercury from ‘Queen’ with the internationally acclaimed soprano Montserrat Caballe. In 1987, Mercury and Caballe recorded the song ‘Barcelona’ for the 1992 summer Olympics that took place in the city of Barcelona in Spain. As you can hear yourselves, the combination of Mercury’s high-pitch voice, with Caballe’s operatic style, and the accompaniment of a full orchestra resulted in a unique pop-operatic song dedicated to the city of Barcelona.

Freddie Mercury, lead singer of the British rock band ‘Queen’, Carl Lender, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

CHAPTER 6 / CLOSER TO THE PRESENT

Even though opera begun its life in royal courts and today we usually enjoy it in opera houses, similarly to the rest of the arts, opera itself mixed with other genres.

As we have already seen in the section about the birth of opera, popular music and dances that people would have recognised from their everyday life were included in the genre from its very beginning.

Naturally, this practice still continues. Elements from our cultures that are popular with the audience are often included in operas. See for example how much richer opera becomes when it mixes with singing styles and instruments that we would normally expect to find in other musical genres. In her opera Angel’s Bone, for example, composer Du Yun used elements from traditional, electronic, pop, as well as church music, while one of the leading characters of the opera sings in the punk style.

The Chinese-American composer Du Yun, photo by Qin Zhen.

Similarly, in her opera TakTakShoo, composer Rene Orth used electronics to alter her singers’ voice as well as ‘musical gloves’– that is, gloves that produce sound according to their wearer’s movement. The music of the opera, in other words, included musical elements we would expect to find in other genres of music and which the aforementioned composers adjusted to the genre of opera.

Beyond the musical component of opera though, stage directors often use costumes and scenery that do not correspond to the historical time of the work. Sometimes they choose to dress the characters in contemporary clothes and to place the action in a different setting to the one originally imagined by the composer and the librettist. In this way we, the audience, can understand better some ideas from the original text that may have changed with time or even come up with new ideas because of this new setting. Whether in terms of music or stage direction, opera partly reflects and reproduces elements of modern culture that the audience enjoys to see on stage. See for example below the Greek National Opera’s recent production of the Marriage of Figaro [Le nozze di Figaro], where the stage director placed the action in a common apartment instead of the original palace.

The Marriage of Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Music direction: Dimitris Chorafas, Alkis Baltas, stage direction: René Terrasson. Olympia Theatre (1979/80).

Snapshot from GNO’s production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro conducted by Vassilis Christopoulos and directed by Alexandros Efklidis (2021)

CHAPTER 7 / INCLUSIVITY

The last box we will open to see how much opera it contains is a relatively new box, whose purpose is to set opera free from its own box and to place little pieces of it in as many other boxes as possible.

Since opera has become part of many people’s life, organisations such as the Greek National Opera run projects aiming to make opera accessible to as many people as possible. And since we do not all live in cities that have an opera house or can afford to pay for singing lessons, these large organisations created educational programmes that invite everyone to participate in opera in any way they wish and are able to. See for example the educational programme ‘Co- OPERAtive’, which invited unaccompanied asylum seeking young people as well as young Athenians to produce an opera together. If you are interested in music, and opera in particular, you can find relevant programmes run by organisations like the Greek National Opera or even write to share your own wishes and ideas with them. They will love to hear from you!

CoOPERAtive: an intercultural breeding ground of opera for teenagers, Greek National Opera, department of Educational and Social Activities.

Why have so many boxes, though? Why not call all of the examples above ‘opera’, since it was the main source of inspiration for musicians, who also named their works ‘opera’? Take a moment to think about the differences between a ‘standard’ work of opera and a rock opera or a song inspired by opera. Are the instruments and the technologies in use the same? Are their themes and their style of performance similar? What audience does each genre attract? Are their differences important? Is their history similar enough so as to not warrant each a distinct name? Just like we store different thing in separate boxes at home to find them more easily, similarly we create musical boxes in order to know where to look for them. Other than this practical issue, the world of music is vast and the boundaries between the different musical genres much more permeable than you can even imagine. All you have to do to explore this world is to go online, listen to Louis Armstrong’s music, and enjoy yet another aspect of opera you could not even imagine existed.

QUIZ / OPERA EVERYWHERE

ACTIVITIES / OPERA EVERYWHERE

Introduction

Connection to the curriculum

– Music class

Main themes

– Song, musical performance

– Repurposing a pre-existing melody

– Creation of original lyrics

Suggested duration

2-3 teaching hours

Educational objectives

– Development of vocal and rhythmic skills

– Creative writing skills

– Development of creativity

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

In Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto (see activity 7) we find the theme from the Duke’s aria “La Donna e Mobile” repeated in different parts of the opera. The aria “La Donna e Mobile” is among the most famous operatic arias and it has also been repurposed for different media including the cinema and TV commercials. Moreover, it is an aria that has been adapted multiple times with changed lyrics. A quick search online can also lead you to a Greek adaptation.

In five steps we will learn the aria, sing it together in class, and in the end we will create our own aria based on Giuseppe Verdi’s music. At the end of this activity learned how an operatic melody can be adapted into a new piece.

Step 1

Listen to the aria “La Donna e Mobile” twice and read the first verse.

Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto “La donna e mobile”, Duke’s aria from the Third Act, soloist: Antonis Koroneos, Olympia Theatre (2008/09).

La donna è mobile

Qual piuma al vento

Muta d’accento

E di pensiero.

Sempre un amabile,

leggiadro viso,

in pianto o in riso,

è menzognero.

Now listen to the first 35 seconds of the aria again while reading the lyrics provided above at the same time.

Step 2

Listen to the following audio file in order to improve your pronunciation:

Εκφορά στίχων στα Ιταλικά από τον μονωδό Νίκο Ζιάζιαρη

When your pronunciation reaches the desired level, read the lyrics as a group clearly and loudly.

Step 3

Read the lyrics imitating the rhythm of the aria. In a stable, comfortable pitch for everyone work on learning the aria through rhythmic recitation, using speech instead of notes. Work on the rhythmic recitation line by line (La donna è mobile / Qual piuma al vento / Muta d’ accento / E di pensiero) and recite the whole verse (8 bars in total).

Ρυθμική απαγγελία από τον μονωδό Νίκο Ζιάζιαρη

Step 4

After learning the rhythm move on to the melody. Following the same process as before, add the element of melody by practicing the aria first line by line and then by singing the whole verse (8 bars).

Απόσπασμα άριας από τον μονωδό Νίκο Ζιάζιαρη

Step 5

After learning and practicing the Duke’s aria “La donna e mobile” in the classroom, work on creating your own lyrics for Giuseppe Verdi’s music individually or in small groups. Substitute the pre-existing text with your own words by Imitating the length of the pre-existing syllables and the aria’s rhythm to make your own aria.

In this way you will see how the melody of an aria describing the charms of a woman can be re-used to express different ideas.