Gender

in opera

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

Chapter 6 offers us a tour across the world of opera through the prism of gender-related issues, ranging from the first female opera singers who dared to step onto the Athenian music scene in 1834 and gender representation stereotypes in opera, to castrati and the #metoo movement. In the following video you can watch Yannis Kalavrianos explaining the significance of reversals in the world of the performing arts, and how in Offenbach’s La belle Hélène the twist is associated with the issue of gender.

Stage director Yannis Kalavrianos discusses the significance of reversals in the world of the performing arts, explaining how in Offenbach’s La belle Hélène a twist is associated with the issue of gender.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / THE “ULTIMATE CORRUPTION”

When the Athenian press announced the construction of a theatre presenting opera in the city in 1834, newspaper Athena responded by voicing concerns about the severity of the moral consequences that would surely follow: Italian female singers on stage.

While the state could not yet secure basic provisions such as schools, argued the newspaper, the ministry was wasting its limited resources on shows of “ultimate corruption” where “the actresses invited from Venice” could spread their harmful morality unchecked.37Εφημερίδα Αθηνά, 17 Οκτωβρίου 1834, στήλη «Διάφορα», σ. 4. In fact, the motive behind the newspaper’s opposition to the theatre was mostly political, and its moralizing position sought to rally political support by confirming its readers’ biases.38Κ. Σαμπάνης 2014, Η όπερα στην Αθήνα κατά την οθωνική περίοδο (1833-1862) μέσα από τα δημοσιεύματα του τύπου και τους περιηγητές της εποχής, σ. 30-31. In this 19th century vignette from Athens, the relationship between gender – broadly understood here as the social manifestation of biological sex– and the political or social issues around public performance on the operatic stage are revealed on multiple levels.

The study of the professional rights of women in the arts, the history of “castrato” singers, and the representation of female, male, intersex, trans, and non-gendered identities, and human sexuality in general on stage, all fall under the subject of how gender has been perceived, portrayed and regulated in the art of opera.

Front page of the 3rd issue of the newspaper Athena by Emmanouil Antoniadis 1791 – 2 August 1863, (1832) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

CHAPTER 3 / GENDER STEREOTYPES

The issue of the presence and representation of the female sex on stage began with the very emergence of the genre of opera.

With musical dramas becoming the first attempt to bring a representation of the social relations between the sexes on a stage where music played an important part, opera also consolidated the musical representation of the sexes in composition. In Claudio Monteverdi’s opera Orfeo, for example, the music sung by male characters reflects the audience’s admiration for men who excel through eloquence and rhetorical skill, while female characters excel through introspection and introversion. In other words, Monteverdi used compositional techniques that signaled the strong ‘masculine’ nature of the protagonist Orpheus through his abilities in rhetoric, while the young ‘feminine’ nature of Eurydice he signaled musically through her innocence and timidity.39S. McClary 1991, Feminine Endings: Music, gender and sexuality, σ. 36, 43-45. And while these stereotypical associations between musical representation and gender would have been understood immediately by audiences at the time, nowadays it is musicological analysis that helps us contextualize the opera, the ideas presented, and decode some of the musical figures, political comments, or even jokes.

As opera became progressively more popular by the end of the 17th century a major social problem became evident: women were appearing on stage in increasing numbers. Surely, you and I don’t have a problem with that; anyone with a talent or something important to express has the right to appear on stage, regardless of their gender! Conventionally, however, in Europe an “honourable” woman was expected to have limited interactions with men in public. Therefore, before 1680 women could be regularly engaged in artistic activities only as members of an aristocratic court.40Rosselli, J. 1992. Singers of the Italian Opera: The history of a profession, p. 61 Their public activities were often accompanied by negative rumours concerning their decency, and they were easy targets for caricaturists who published derogatory sketches and insinuations about their private lives. As we saw in the example above, it was not uncommon for a publication to defame a singer in order to rally political support by readers with similar prejudices. Until 1750, in Italy where opera was flourishing at the time, most female singers developed short careers and were usually under the protection of a powerful man.41Sadie, S. 1997. The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, vol. 4, p. 480

Margaret Hughes (1630-1719) is considered one of the first female professional actresses, Peter Lely, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

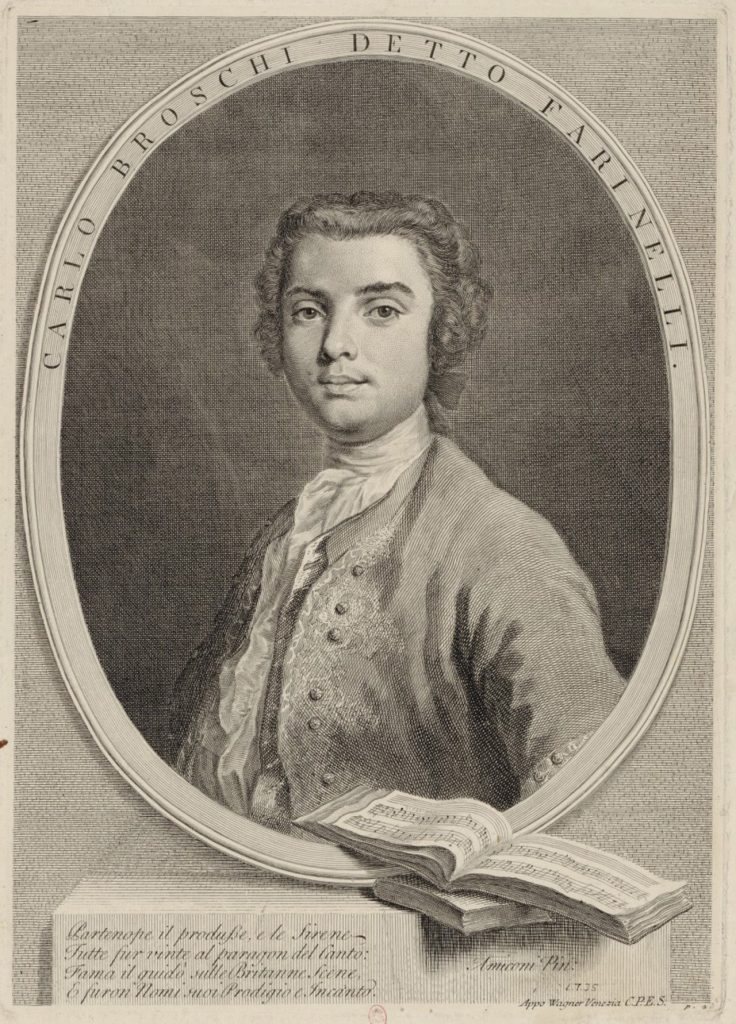

CHAPTER 4 / CASTRATI

Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi (1705 – 1782) the famous 18th century “castrato” who went by the stage name Farinelli, Joseph Wagner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Wait a minute, you will protest, we have already talked about Orfeo ed Euridice, and we also know so many other operas with female roles, how is it possible if so few women were allowed on stage?

It may appear strange to you, but since women had to stay at home and constantly dust the tabletops, female roles were performed by men. The term “soprano”, which today describes women singing in the high tonal ranges, was used both for female singers and for a distinct class of male singers that has been discontinued since the 1830s.

These singers were called “castrato” singers and originally sang only in churches, where women were strictly forbidden to sing. As high – but not female – voices were in demand for the performance of church hymns, a new musical specialisation emerged in monasteries: young boys whose voice mutation was prevented by genital surgery, in order to be musically trained to perform high-pitched parts.42Sadie, S. 2001 (2nd ed) The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 5, p.267 In this way, the delicate tone of these boys’ voices was preserved even after puberty. Young castrato singers received intensive musical training in singing, music theory and musical instruments, often resulting in a greater degree of musical specialization than women of the same vocal ability, whose educational opportunities were limited because of prejudice against their sex.

Between 1680 and 1720, castrato singers enjoyed a golden age on the operatic stage as audiences and the aristocracy throughout most of Europe appreciated their special vocal abilities. The leading male roles were written for their type of voice and they enjoyed the support of powerful opera patrons.43Sadie, S. 1997. The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, vol. 1, pp. 766- 767 Especially during the periods when women were banned from the stage in the 17th and 18th centuries, high-pitched female roles were performed by “castrato” singers. Nevertheless, the majority of “castrato” singers continued to be employed partly or exclusively by the church.44Rosselli, J. 1992. Singers of the Italian Opera: The history of a profession, p. 41

Historical recording of Ave Maria by Franz Schubert by Alessandro Moreschi, known as the last “castrato”.

In terms of stage presentation, cross-dressing was common when there was need for a man to play a female role, and until the mid-18th century both men and women would play roles of the opposite sex for musical or dramatic purposes regularly. Apart from instances of female roles sung by castrato singers, men also appeared in female costume when the plot demanded it, and women played male characters that sung in the higher vocal register– see for example the role of Prince Orlofsky from Johann Strauss II’s operetta Die Fledermaus, below.

Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss II. Conductor: Michalis Oikonomou, stage direction: Alexandros Efklidis, Prince Orlofsky: Artemis Bogri, Stavros Niarchos Hall (2020)

CHAPTER 5 / WOMEN TAKE THE LEAD

Jenny Lind (1820-1887), one of the most famous opera singers of the 19th century Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Times changed, however, and a shift in public taste in combination with the gradual turn of Italian public opinion against surgical intervention for musical reasons, led to the disappearance of “castrato” singers from opera from the 1830s.

Since the beginning of the 19th century, and especially after restrictions on female performance on stage were lifted, female sopranos experienced their own golden age that lasted until the first decades of the 20th century.45S. Rutherford, The Prima Donna and Opera, σ. 4. Despite society’s hostile attitude and their frequent vilification by journalists and music critics, the profession of opera singer was one of the first professions to give some women independent careers in music. Through the persistence of women and the support of some colleagues – composers, conductors, singers – who recognized the distorted association between moral decency and the right of women to practice their profession in public, the right of women to a career in singing was accepted earlier than other musical professions. Unlike other musical instruments, where women were employed exclusively as music teachers and positions in orchestras were strictly reserved for men until as recently as the 20th century, the profession of “soprano” gave female professional musicians the opportunity to become financially independent and to pursue musical careers as early as the 19th century.46από την Φάνη

And while here we have focused – perhaps unfairly – exclusively on the historical development of the profession of female singers, inequality in the arts concerns equally societal prejudice against LGBTQIA+ identities, disability and race. Moreover, bias and unequal treatment in the workplace similarly affects workers in the technical professions of opera, namely the people who support opera productions without performing on stage. In the article “Women in technical theatre, let’s change our future” published by London’s Royal Opera House in 2021, deputy director of technical and production Emma Wilson shared some of the difficulties faced by women in technical jobs in opera. Among them she counted being underestimated by male colleagues, limited childcare support, fewer opportunities for career progression, and the gender pay gap. She even reflected upon the fact that during her educational visits in schools, she noticed how girls still considered some technical professions in opera as “boyish” and could not imagine themselves in one.47https://www.roh.org.uk/news/women-in-technical-theatre-lets-change-our-future

The historically unequal treatment of women on and off the operatic stage, has inspired movements against the gender pay gap in the arts, as well as social movements such as #MeToo that monitor the behaviour of organisations and businesses on gender-related issues. Opera, like any other art-space, should encourage all humans, regardless of gender identification, race, nationality, sexual identity, physical and mental constitution, and disability, to express themselves and share their talent with the public. Similarly, it must protect their right to work in technical positions without prejudice, and secure the equal treatment of all its members. Each society defines its own morality and it is important that our own legacy becomes the message that, at least in art, we actively try to support all humans because – and not in spite of the fact that – we are all different.

QUIZ / GENDER IN OPERA

ACTIVITIES / GENDER IN OPERA

Introduction

Connection to the curriculum

– Music

– Social and Political Education

– Art class (additional activity)

Main themes

– Libretto

– Storyboard

– Gender stereotypes in the arts

Suggested duration

2-4 teaching hours

Educational objectives

– Understanding the social dimension of art

– Developing critical thinking

– Encouraging abstract thinking

– Raising awareness on gender issues

– Development of creativity

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

In the section “Gender in Opera” we focused on the professional world of music, opera and theatre, discussing the position that women have historically occupied onstage and offstage. In the following activity we will examine how women’s position in society is portrayed in Giacomo Puccini’s famous opera Madama Butterfly.

– Could we imagine a different twist in the story line of Butterfly?

– Why are the most famous opera heroines mostly tragic figures?

The aim of this activity is to enrich our classroom discussions about the representation of women in the arts.

Step 1

Read the synopsis of the opera Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini in class:

The story of the opera Madama Butterfly begins when Lieutenant B. F. Pinkerton, a lieutenant in the United States Navy, arrives in the port of Nagasaki. With the help of Goro, a Japanese professional matchmaker, he “marries” 15-year-old, poor geisha Cio-Cio-San, known by the nickname Butterfly. Pinkerton informs American consul Sharpless that, under Japanese law, for him the union is not binding and it can be dissolved at any time. In vain, Sharpless points out to the officer that for the teenage Cio-Cio-San the ceremony is a serious matter. The wedding day arrives with the fifteen-year-old geisha arriving at the ceremony presenting Pinkerton with her few belongings, including the ceremonial knife with which her father killed himself. The geisha’s priest and uncle, Bonze, appears at the ceremony and curses her in front of everyone for renouncing her faith. Butterfly, believing herself to be legally married to Pinkerton, converts to Christianity, abandons her Buddhist faith, and isolates herself away from friends and relatives because of this marriage. Pinkerton abandons Butterfly, but promises her that he will soon return and take her with him to America.

Three years later, Butterfly, having given birth to her son with Pinkerton, is still waiting for his return, shunned and forgotten by everyone. Her only companion remains her maid, Suzuki. When she gets informed that Pinkerton is about to arrive, she decorates their house to welcome him, and waits for him all night, wide awake. Pinkerton eventually returns to Japan, not alone, but with his legal wife, Kate. When he is informed of his son’s existence, he decides to take him away from Butterfly. When she sees his new wife and is informed that Pinkerton will no longer return to her, she accepts her fate and even agrees to give up her son. She requests that Pinkerton himself receives her son and decides to end her life. Wanting to prevent such evil, Suzuki sends her son close to her, but Butterfly has made up her mind. She bids a heartbreaking farewell to her son, blindfolds him and commits suicide just before Pinkerton’s arrival.

Step 2

Watch the following excerpts from two different productions of Madama Butterfly by the Greek National Opera.

Excerpt from the intermezzo of Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini. Conductor: Lukas Karytinos, stage direction, sets and costumes: Hugo de Ana, Odeon of Herodes Atticus, 2017

Excerpt from the GNO production of Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini. Conductor: Lukas Karytinos, stage direction, sets and costumes: Hugo de Ana, GNO TV, 2020

Step 3

Now that you have a better idea of the story of Butterfly, you can lead a discussion in class around the following questions:

1. Why didn’t Pinkerton return to Nagasaki to bring Butterfly with him to America?

2. Why did Butterfly agree to give her child to Pinkerton?

Step 4

Based on what you have read, seen and discussed, can you create, either individually or in small working groups, a new story line for Butterfly?

A new proposal, a different development for the heroine, starting at whichever point in the story you wish and taking the story in any direction you think would be most interesting to you or your group.

To what extent do you consider it necessary for the story of Butterfly to have a tragic ending? To what extent does the gender of the characters also determine their role in the development of the story?

Additional activity:

After you have concluded and written your own story about Butterfly, you can, with the help of an arts teacher, create a graphic novel or a comic strip.