Opera in the

course of time

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

The chapter Opera in the course of time is a non-linear account of the history of opera revolving around the changes that shaped the genre through the ages, in relation to and in dialogue with the social background of each era. Composer Kornilios Selamsis describes in the following video the special nature of the opera Offenbach’s La belle Hélène, as well as the ways in which this opera involves the audience.

Ο συνθέτης Κορνήλιος Σελαμσής μιλάει για το πως ένα σύγχρονο έργο όπερας μπορεί να συνομιλεί με ένα κλασικό.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / A VISIT TO THE OPERA

Check your coat in the cloakroom, take staircase number two, door number one, find row M and you’ve finally taken your seats– 14 & 15. The lights are off, the music starts – you are seeing La traviata – and you whisper to your friend that the staging looks wonderful.

The gentleman behind you complains, “We are in the opera house, show some respect, please be quiet”. Although the gentleman’s reaction you find a bit over the top, you remember that the theatre is usually a quiet place, you remove your hat so as not to disturb those behind you, and you withhold your enthusiasm until the interval.

As many important dates as we may try to remember when we read the history of opera, it is equally useful to remember that even our habits in the opera house form part of the history of the art. Read the previous paragraph again and try to guess how the experience of attending the opera might have been different in the past.

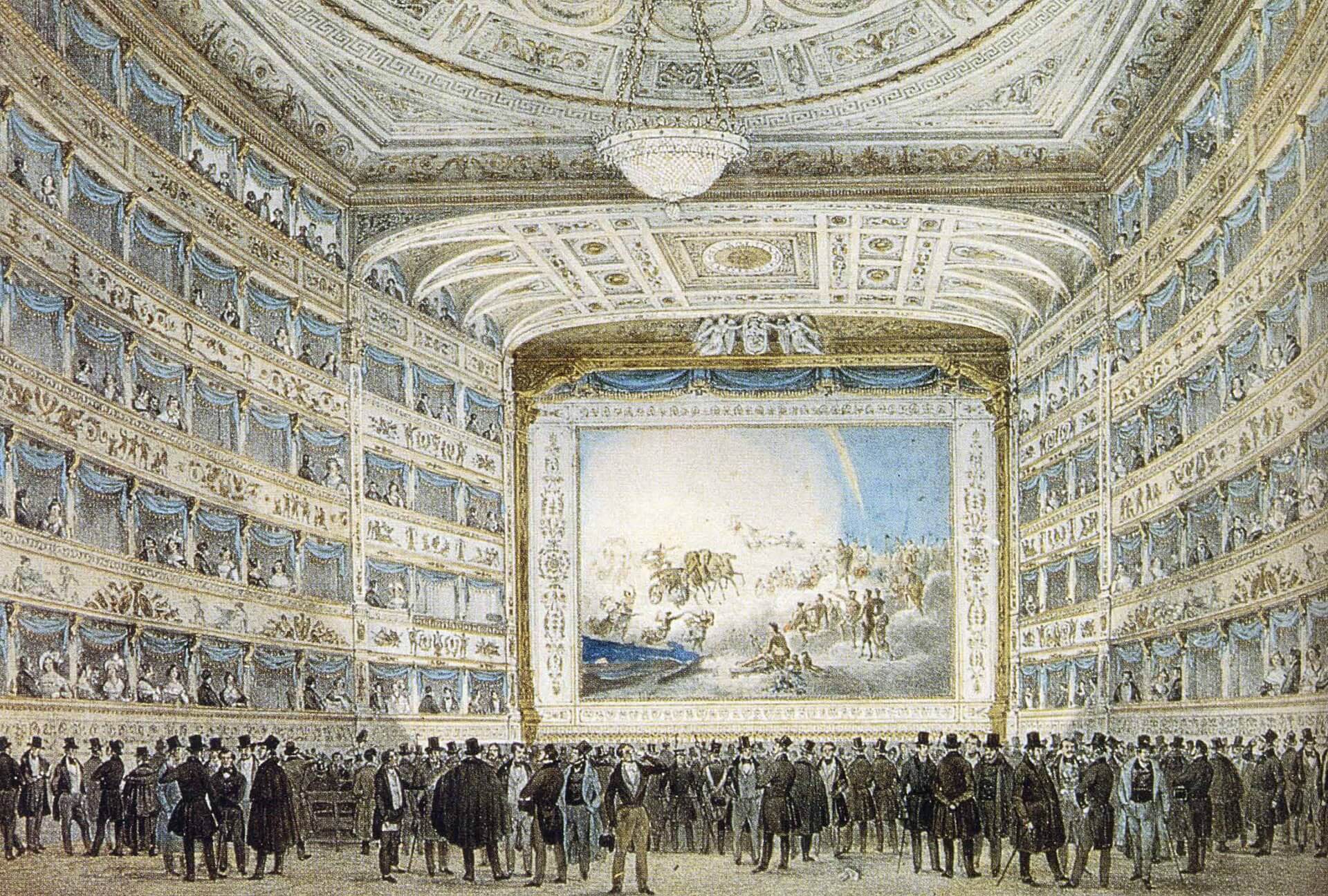

Even if you don’t look at the modern costumes and you don’t listen to the music, the environment of the theatre, the position of your seats and the fact that you have removed your hat show, not only that you bought your ticket in 2023, but also how operatic traditions determine the way we enjoy the art. As strange as it may appear today, it has not always been quiet at the opera. In fact, many operatic works have been composed explicitly to combat the noise that used to prevail in the auditorium.10Abbate, C., Parker, R. 2012. A history of opera: the last 400 years, p. 59 Therefore, while the way we see opera betrays that we live in the 21st century, the way we listen to it can “transfer” us directly into the past.

Theatre La Fenice, Venice (1837), Museo Correr, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

CHAPTER 3 / THE ‘UNIVERSAL’ ARTWORK [GESAMTKUNSTWERK]

It is a widely known historical fact that composer Wilhelm Richard Wagner chose the small town of Bayreuth in Germany in 1876 to build his own ‘music temple’. A dimly lit space aspiring to perfect acoustic standards, where music-lovers would congregate to listen attentively to his music.11Snowman, D. 2009. The Gilded Stage: a social history of opera, pp. 196- 197

This venue was intended for compositions of the highest standard, presented as ‘complete’ musical, theatrical, poetic, scenic and ideological spectacles; ‘Perfect’ operas for a ‘perfect’, silent and serious audience. A few years earlier, an absolutely unserious audience in Paris had heckled Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser because he had placed the ballet in the wrong part of the performance. And since a significant part of the audience only came to the opera house for the second act and then walked in and out of the auditorium at will, they missed the ballet, heckled the performance, and exposed something that composers and art critics had been complaining about for years;12Abbate, C., Parker, R. 2012. A history of opera: the last 400 years, p. 282 opera was more often a place of socialization and entertainment than a space where audiences listened attentively (and seriously!) to music.

Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883) by Pierre Petit (1861), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Music lovers may have been partly justified in their complaints, yet the incredible variety of operatic works and the popularity of the spectacle in the 19th century show the public to have been far from indifferent to the art. As you will notice from the titles of the works in the following list, apart from the variety of nationalities of the featured composers, opera in the 19th century had emerged as a cultural sector that supplied its eager audience with works for all kinds of tastes. In Romantic opera, emphasis was put on emotions rather than rationalism, the characters became entangled in supernatural encounters, and traditional music was often used to highlight the national identity of the locality where the work was set.13Arnold, D. (ed.) 1983. The New Oxford Companion to Music, vol. 2, pp. 1581- 1582

Video excerpt from the production of Richard Wagner’s emblematic opera Tristan and Isolde by the Greek National Opera. Conductor: Myron Michailidis, Stage direction, set and costume design: Yannis Kokkos. Megaron-Athens Concert Hall, Alexandra Trianti Hall, 2015

Giacomo Puccini, Tosca, “Qual occhio al mondo”, Cavaradossi-Tosca duet from the first act, soloists: Misha Didyk and Kristine Opolais, Olympia Theatre (2006/07).

Richard Wagner, Tannhäuser, “Inbrunst im Herzen”, aria of Tannhäuser from the third act, soloist: John Treleaven, Megaron-Athens Concert Hall (2008/09).

Giuseppe Verdi, Nabucco, “Oh! Chi piange”, aria of Zaccaria from the third act, soloist: Dimitri Κavrakos, Olympia Theatre (2006/07).

As you can see in the following list, 19th century operatic plotlines catered to all tastes: it includes comedies and light romances, plays on historical or mythological themes, musical tragedies and adventures. Wagner’s intention, therefore, was to highlight the importance of music over the other arts that comprise opera. It’s great that we enjoy the sets, the costumes, the text and the plot, he was saying, but let’s pay some attention to the music, too!

CHAPTER 4 / OPERA SERIA - THE “SERIOUS” OPERA

The carefree behaviour of the audience was not an exclusive characteristic of the 19th century, nor was it a complaint expressed by musicians only. From as early as the 1680s, authors had already been expressing similar concerns of their own.

Opera, they said, had become light entertainment, the audience was enchanted by the sets and popular melodies, singers were little more than well-paid superstars, and no one paid attention to poetry and ethics; a total depreciation of literature in favour of music, and a society on the verge of collapse. The movement that gave birth to opera seria – ‘serious opera’ – in the 18th century aspired to reform opera but to the opposite direction from Mr Wagner’s push for more music. With themes drawn from ancient Greek and Roman myths, characters experiencing moral dilemmas and struggling with their emotions on stage, strictly structured arias, more poetry, less music and fewer comic characters; a didactic, artistic and moralizing spectacle. Musically, this was expressed through the use of the recitativo secco, the reduction of duets and ensembles, and in many cases through the absence of a choir. And while this significant reduction of musical variety may have had you – and certainly me – avoid opera, the clear moral and political messages, the presentation of benevolent monarchs, and the development of the aria structure made opera seria one of the most successful opera genres in Europe.14Abbate, C., Parker, R. 2012. A history of opera: the last 400 years, pp. 77-78

Why did the positive portrayal of the monarch render opera seria more popular?

George Frideric Handel, Alcina, “Ombre pallide”, aria of Alcina from the second act, soloist: Mata Katsouli, Olympia Theatre (2004/05).

George Frideric Handel, Xerxes, “Crude furie degli’ orrridi abissi”, aria of Xerxes from the third act, soloist: Mary-Helen Nezi, Olympia Theatre (2002/03).

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714 – 1787) by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Most works of opera seria from this period are not performed often today. An exception to this are the works of Christoph Willibald Gluck, who introduced major reforms to opera seria, and like all men of his social class he wore a white wig with little curls.

Influenced by the French genre of opéra comique, in the opera Orfeo ed Euridice, Gluck and librettist Ranieri de’ Calzabigi presented a work with a simpler and more direct text, and music that emphasized this directness in the recitative and arias.15C. Abbate – R. Parker 2012, A History of Opera. The last 400 years, σ. 108-109. As you can see, things were now both very serious and more immediate. Of course, theatres do not appear to have been at all more quiet – they were still places for socialising and the audience played chess while waiting for their favourite aria – but the genre of opera seria had taken over the minds of 18th century composers.16D. Grout 2003 (4η έκδ.), A Short History of Opera, σ. 222. Or maybe not?

Excerpt from the GNO production Orfeo ed Euridice του Christoph Willibald Gluck. Donductor: George Petrou, stage direction: Stephen Langridge, Olympia Theatre, 2007

What other composers who wore white wigs with little curls do you know and which of their works are your favourites?

CHAPTER 5 / MOZART AND OPERA BUFFA

![Βόλφγκανγκ Αμαντέους Μότσαρτ [Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart] (1756-1791).](https://operabox.nationalopera.gr/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2.11_Wolfgang-amadeus-mozart_1_RD-min-799x1024.jpg)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 – 1791) by Barbara Krafft, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

As we saw previously, in order to bring the moral messages and the poetry at the centre of the audience’s attention, the creators of opera seria proposed a form of opera with fewer comic roles and less ‘light’ music. After this sharp division between serious and comic characters, the comic roles and their ‘light music’ acted accordingly: they packed up their stuff and moved into their own kind of opera. In other words (more serious), the creation of the strictly defined opera seria resulted in the development of its comic parts (intermezzi) into an independent genre of opera. The genre of opera buffa (later dramma giocoso) gradually managed to surpass opera seria in popularity, presenting a wide range of characters from different social classes, who expressed their identity through diverse musical textures.17Abbate, C., Parker. 2012. A history of opera: the last 400 years, pp. 122-123 It was through this style that perhaps the most important opera composer in history expressed himself, combining humor with poignant political and moral commentary in his works. And he also wore a white wig with curls.

For Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, music was the most important component of opera, the expressive means that gave life to the characters of his works and communicated his social and political ideas directly to the audience. Mozart ‘spoke’ through his music, that is, he portrayed the personalities of his heroes in the music rather than rely on the text or their stage presence. Mozart’s talent is particularly evident in the opera buffa Le nozze di Figaro, with Lorenzo Da Ponte as librettist, and in the Singspiel Die Zauberflöte with Emanuel Schikaneder as librettist.

In the opera Le nozze di Figaro, all sorts of things happen: love affairs, power games, intrigue, reconciliations and farces. The ideas of the Enlightenment about equality are reproduced in a mixture of musical humor and social commentary on the relationship between servants and the aristocracy. The characters present realistic human complexity, as Mozart’s musical representation lends them emotional depth and a personality that makes them into something more than ‘social models’ or theatrical characters.18Grout, D. 2003 (4th ed.) A short history of opera, p. 315 Listen for example to the following excerpt from the opera Le nozze di Figaro. What do you understand about the central character of the opera from this short fragment?

Excerpt from the GNO production Le nozze di Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Conductor: Vassilis Christopoulos, stage direction: Alexandros Efklidis, GNO TV, 2021

This opera, along with the dramma giocoso Don Giovanni and the opera buffa Così fan tutte ossia La scuola degli amanti, are Mozart’s three collaborations with Da Ponte, which stood out among the other operas of the period for their musical and literary genius. They are works in which the music and the text communicate the ideas and the humor of their creators through great craftsmanship.

Excerpt from the opera Don Giovanni by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Conductor: Daniel Smith, stage direction: John Fulljames. An international co-production of GNO with Göteborg Opera and the Royal Danish Opera, GNO TV, 2021

In Mozart’s last opera, the ‘Singspiel’ Die Zauberflöte, the composer’s Freemason ideals gave symbolic dimensions to the main characters and expressed the core ideas of the Enlightenment. In this imaginative adventure about the rescue of princess Pamina, equality between genders and social classes is emphasized, and there even appear to be some traces of racial equality. The genre of ‘Singspiel’ itself adheres to the ideals of the Enlightenment as well, as it was not performed in High German, but rather in the language that ordinary people spoke and understood, and it was considered the most inferior among the opera genres.19Taruskin, R. 2009. Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, pdf p. 529 [βρες hardcopy]

Note below, the tremendous variety of musical textures Mozart used in order to portray his characters. The character of Papageno, a bird hunter for the Queen of the Night, is musically enriched with elements of German folk music.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, aria of Papageno “Der Vogelfänger” from the first act, soloist: Haris Andrianos, Olympia Theatre(2012/13).

Prince Tamino’s romantic arias highlight his role as a hero and combine musical elements that were popular in Italy and Germany.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, aria of Tamino “Dies Bildnis ist besonders schön” from the first act, soloist: Antonis Koroneos, Olympia Theatre (2012/13).

Whereas Zarastro and the Queen of the Night – with her famous aria – express themselves in the style of opera seria.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, aria of the Queen of the Night “Der Hölle Rache” from the second act, soloist: Vassiliki Karayanni, Olympia Theatre (2012/13).

Who were the Freemasons of Mozart's time and what were the main ideas of the Enlightenment?

CHAPTER 6 / A MUSICAL CELEBRATION?

Our last stop before seeing how opera developed in the 20th and 21st centuries will be at the century when it all began. Back when there was definitely a lot of noise in the theatre, a lot of music and no white wigs at all.

As you saw in the section “The birth of opera”, the beginnings of opera are conventionally placed between 1573 and 1587. This was when Camerata‘s experiments led to the first musical dramas and the first operatic works were presented after the influence of composer Claudio Monteverdi.

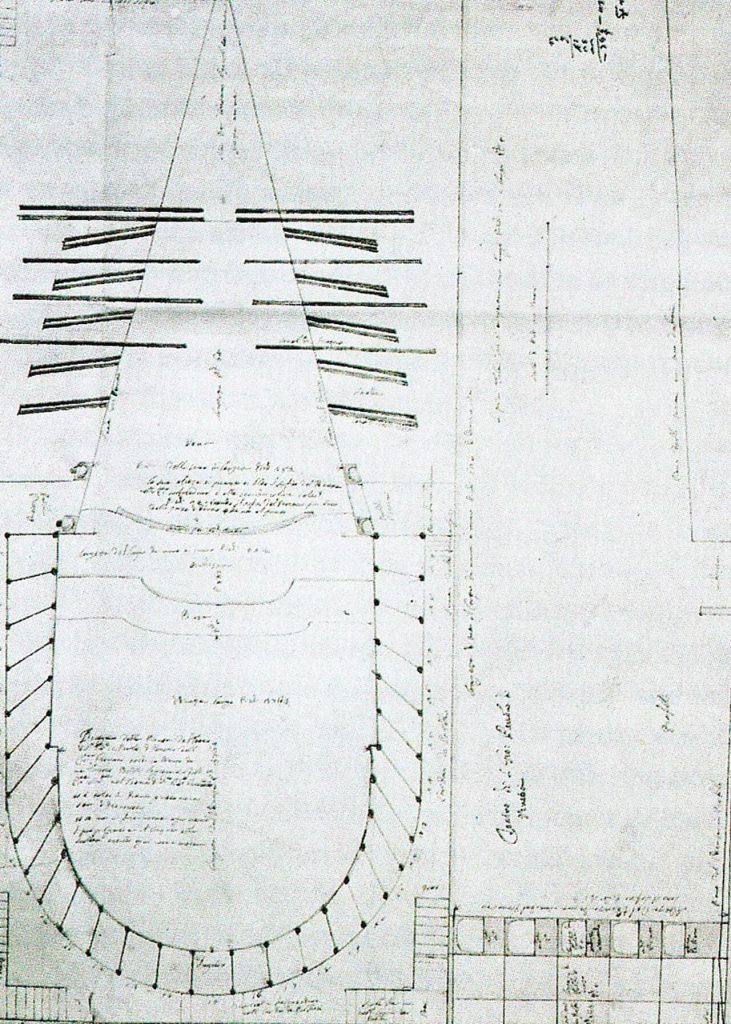

And here we can finally admit it: the supporters of opera seria were right after all. During the 17th century, opera was a great musical celebration. Not because the public did not respect poetry, but because it was in part its contact with the public that gave opera the form in which we understand it to this day. So, while the theoretical experiments of Camerata were indeed important, the results of these experiments were “academic” and only concerned the limited audience that attended them, i.e. the aristocracy in theatres within palaces.20R. Τaruskin 2009, Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, pdf, σ. 23. [βρες hardcopy] This situation was to change radically after the creation of Teatro San Cassiano in Venice in 1637, a theatre that relied on the financial support of the public and catered to their preferences.

Stage plan of the theatre Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice in the mid-17th century, Carlo Fontana 1634-1714, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The mid-17th century may feel like a different world from our perspective but you will certainly recognise some similarities with our modern society in the way opera was treated. Just like today when a popular film is released most people who can afford a ticket go to the cinema, so was the case in 17th century Venice. Between 1637 and 1700 more than 350 operas were staged in the 9 theatres that were operating especially for this purpose, while from 1680 onwards, the city –which had a population slightly larger than that of Volos today– maintained 6 opera companies.21Grout, D. 2003 (4th ed.) A short history of opera, pp. 83- 84 In this public space, opera was shaped to satisfy its wider audience, the theatre became a venue of musical entertainment with the preferences of the public determining the development of the genre, while at the same time its relative autonomy from aristocratic preferences allowed the development of anti-aristocratic political elements in the genre.22Τaruskin, R. 2009. Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, pdf p. 25 [βρες hardcopy] From the middle of the century onwards, many more Italian cities acquired theatres that presented opera, and the genre soon spread to the neighbouring Germany and to France, where it was adapted to the respective local musical culture and the taste of the audience. Thus, opera, born as an experiment borrowing elements from Italian musical culture, soon spread throughout Europe and its colonies, Russia, the Ottoman Empire and to the Kingdom of Greece in the 19th century.

How important is public acceptance for an art such as opera?

Listen to the following examples of opera music from different periods and discuss the differences that you notice.

Giuseppe Verdi, Μacbeth, aria of Banco “Come dal ciel precipita” from the second act, soloist: Dimitri Kavrakos, Olympia Theatre (2002/03).

Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto, aria of the Duke “La donna e mobile” from the third act, soloist: Αntonis Koroneos, Olympia Theatre (2008/09).

Giuseppe Verdi, La traviata, aria “Sempre libera” from the first act, Olympia Theatre (2005/06).

Charles-François Gounod, Faust, Soldiers’ Chorus from the fourth act, Megaron-Athens Concert Hall (2011/12).

Vincenzo Bellini, Norma, aria of Norma, “Casta diva” from the first act, soloist: Dimitra Theodossiou, Olympia Theatre (1998/99).

Antonín Dvořák, Rusalka, aria of Rusalka “Vidis je, vidis” from the second act, Olympia Theatre (2008/09).

Giacomo Puccini, Τosca finale “Tre sbirri… una carrozza…” from the first act, Olympia Theatre (2006/07).

Gioacchino Rossini, L’italiana in Algeri, duet Isabella-Mustafà “Oh che muso! Che figura” from the first act, Olympia Theatre (2005/06).

CHAPTER 7 / FROM NOISE TO SILENCE

The issue of silence in theatres concerned music theorists, it contributed to musical reforms, it was often enforced through the policing of theatres, and it was established as a tradition by the end of the 19th century.

The case of conductor Arturo Toscanini, who introduced new rules in Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 1898 to achieve long-term changes in the behaviour of the audience, is illustrative. Toscanini dimmed the lights in the auditorium to direct the audience’s attention to the stage and he banned spontaneous applause and elaborate hats that blocked the view.23Cowart, G. “Audiences” in Greenwald, H. M. (ed.), 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Opera, pp. 670- 671

In the quiet theatre of the 20th century, after 300 years of operatic tradition and numerous musical conflicts, the silent audience witnessed incredible musical opulence, which partly reflected the monumental political and cultural developments of the past century. The European National Schools of music, which demanded the recognition of the value of works that did not belong to the Italian, French or German traditions, highlighted other local musical idioms from around the continent and the traditional music of their respective countries. Notable among those are Antonín Leopold Dvořák’s musical fairy tale Rusalka (1901), the operas Jenufa (1904) and The Cunning Little Vixen (1924) by Czech composer Leoš Janáček, and the opera Bluebeard’s Castle (1918) by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

Leoš Janáček, The Makropoulos Affair, introduction of the opera, Stavros Niarchos Hall – Greek National Opera (2017/18).

Excerpt from the GNO production Bluebeard’s Castle by Béla Bartók. Conductor: Vassilis Christopoulos, stage direction: Themelis Glynatsis, costumes: Leslie Travers, Stavros Niarchos Hall 2023

Excerpt from the GNO production Bluebeard’s Castle by Béla Bartók. Conductor: Vassilis Christopoulos, stage direction: Themelis Glynatsis, costumes: Leslie Travers, Stavros Niarchos Hall 2023

From the point of view of compositional techniques through which composers attempted to experiment on the texture of the music, Claude Debussy presented his impressionistic opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) and Alban Berg staged the operas Wozzeck (1925) and Lulu (1937), which were composed according to the principles of the twelve-tone technique. In the first decade of the century, the Romantic and early-modern music composer Richard Strauss presented the operas Salome (1905) and Elektra (1909). In Russia, Dmitri Shostakovich was politically persecuted for his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in 1934, while in the field of politicised music Kurt Weill presented the popular Die Dreigroschenoper in 1928, based on a text by Bertolt Brecht. In the last quarter of the century, American composers such as Philip Glass and John Adams began to represent minimalism in their operas Einstein on the beach (1976) and Nixon in China (1987), respectively. If you are curious to see what has been happening in the world of opera in recent decades, you can try the Shakespearean The vision of Lear (1998) by Japanese composer Toshio Hosokawa or the opera L’amour de loin (2000) by Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho. Similarly to the past, contemporary opera borrows themes from literature, the everyday life, and the world of imagination to present extravagant shows on stage, in order to entertain, stimulate and inspire the audience. From the very beginning of opera’s existence, opera producers have used the most advanced technologies of their time to captivate audiences with spectacular sets and stage mechanisms that seem to make the impossible possible. Nowadays, with the development of information technology, modern opera productions use 3D holograms, on-stage projections and spectacular lighting to offer the music and text additional dimensions. Opera works from the world’s greatest opera houses are now available online and are more accessible than ever.

Excerpt from the introductory scene of the opera Nixon in China by John Adams. Conductor: David Parry, stage direction: Peter Sellars, Megaron – Athens Concert Hall, Alexandra Trianti Hall, 2007 (a production of the English National Opera)

Opera is a multi-media spectacle that has evolved in several countries simultaneously, targeting audiences with diverse musical, scenic, literary, moral and political tastes. Its history is a developing narration of the changes, success, failures and the many different directions it has taken through time. It is a story that recounts how society shaped opera and how opera in turn shaped society. We, the audience that is attending opera, are as much an integral part of its history as the singers, directors, composers and conductors, who constantly demand that we remain quiet. Lately, there are rumours that absolute silence in the opera is being reconsidered, and measures against restless audiences are being eased. So, who knows, maybe in the future you and I could meet at a performance of La traviata for a game of chess.

The Artist on The Composer, visual art installations’ programme in cooperation with the organisation ΝΕΟΝ, Νikos Navridis, Stavros Niarchos Hall – Greek National Opera 2018/19

QUIZ / OPERA IN THE COURSE OF TIME

ACTIVITIES / OPERA IN THE COURSE OF TIME

Introduction

Connection to the curriculum

– Music

– Social and Political Education

– Physics (if the activity concerns acoustics, it can be linked to thinking about sound waves)

Main themes

– History

– Art and Society

– Αcoustics

Suggested duration

1-2 teaching hours

Εducational objectives

– Understanding of the social dimension of art

– Development of critical thinking

– Development of critical reflection skills

– Cultivation of listening

– Development of creativity

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

In this section we have seen how social conventions have had a decisive impact on the evolution of opera. For example, a different kind of music and production might work in the ‘musical temple’ built by Wilhelm Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, Germany, than in the theatres of Venice during the 17th century where the audience wandered freely, played chess24Grout, D. 2003 (4th ed.) A short history of opera, p. 222 and entered and left the theatre at will. How could the audience listen attentively to the music in a noisy theatre? And could noise or silence in the theatre affect whether someone attended a comic or a dramatic opera? Could it be that a composer took into consideration, not only the space, but also the circumstances under which their work would be presented to the audience?

The aim of this activity is to explore the dynamic relationship between an artistic work, the space where it is performed and the audience itself.

Step 1

For this activity, you can make use of the musical abilities of your students. If a live musical performance is not possible, you can follow the alternative option presented at the bottom of this page

Discuss with the students who play an instrument and/or sing about which pieces (or excerpts) they could perform live to the rest of the class. Select together with them two pieces with different styles. For example, one might be a dance piece and the other a lament, or a piece of pop music and an atmospheric soundtrack. Give students 2 or 3 weeks to prepare their pieces before starting the activity. You might encourage students who play a musical instrument to perform at least a short excerpt from a piece.

Step 2

When the students are ready for the live performance, choose two or three of the following places for the presentation.

– The classroom where your lesson already takes place

– The schoolyard

– The events-hall or theatre of your school

– An area of the school building where there is a lot of echo (a corridor, stairwell or the gym)

– A small utility room or a small office

Note: the overall duration of the performance should be short so that it can be repeated in different places within the same teaching hour and leave time for a brief discussion. Even five minutes of music are enough for the activity.

Step 3

Using the following questions as discussion prompts, lead a discussion with your students.

– Which space had the best acoustic quality for each piece of music?

– How important was the placement and the position of the audience? Was the audience seated or standing?

– Was there an optimal audience arrangement for each piece of music?

– Did the audience participate, or were they just attending the activity?

– Were there external factors that distracted you? For example, when you performed the activity in the schoolyard, were all attendees able to concentrate?

– Was it preferable to have a quiet place where the public attended the performance seated, or were there occasions when the active participation of the public was essential for the success of the activity?

Alternative versions of the activity:

1. Digital playback of audio files

If there is not the option of live music, you can use a portable audio player and concentrate on the acoustic element of the activity. An simple solution would be to use a bluetooth speaker that can be connected to a mobile phone, tablet or computer. Pay attention to the way that the sound can change when you are in a large space with strong echo. Focus on the acoustics of each room and follow all the steps as outlined above.

2. For the lesson of Physics – Sound waves

The activity of this unit can be useful for teaching the theory of sound waves in 3rd Grade Physics. As every space will have unique acoustics, an activity where the same sound is reproduced in different spaces demonstrates the qualities of sound waves. Through this activity you can explore the ways in which sound waves propagate, are absorbed, diffracted or reflected on different surfaces. For example, why do we hear the same sound louder when we occupy an empty space than when it is filled with objects or humans? What exactly takes place in our school corridor that makes sounds become longer, and as a result mix with each other?