The Beautiful

Helen

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

The Beautiful Helen (commonly known as the Helen of Troy), the woman whose beauty alone, as alleged by many over the course of centuries, was enough to cause the Trojan war, is not just a mythical figure. The Beautiful Helen, who has inspired many artists, from Homer to Euripides and from Offenbach to Kornilios Selamsis, is the same figure that has sparked so many ideas and incentives for artistic creation. The librettist Alexandra K* presents the Beautiful Helen as she imagined and moulded her for the opera Offenbach’s La belle Hélène.

The librettist Alexandra K* presents the Beautiful Helen as she imagined and moulded her for the opera Offenbach’s La belle Hélène.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / A HUMAN BEING OR A SYMBOL?

Let’s now talk about an idea called “Helen”. You may already be familiar with her from school, or from the opera we are discussing here, or you may not know her at all. But “Helen”, the radiant, the femme fatale, the envied, the cursed, the beautiful Helen, is a mythical woman of the antiquity who, just like many others, was created by ancient poets and philosophers to address the issues and concerns of each period in which she reappeared.

“Helen” was beautiful and cursed throughout antiquity, not because of any harm she herself caused, but because of the harm caused by her beauty. A woman’s “power” to destroy society through her eroticism and the “unrestrained” passion she “provoked” in men was a frequent narrative in ancient Greek tradition.

Helen of Troy, Evelyn De Morgan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Control of women’s independence by their socially superior men was considered almost imperative and women in ancient Greece never acquired civil rights; they always remained under the guardianship of a male family member, like children.1Blondel, R. 2013. Helen of Troy: Beauty, Myth, Devastation, pp. 10- 12

Helen of Troy, Henry Hintermeister, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

A sculpture of Sappho by Claude Ramey (1801), Louvre Museum, Claude Ramey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

At the same time, however, women were considered a source of considerable power. Through lucrative marriages, assets were transferred and new citizens were born. Attention! Neither of these two facts favoured women themselves, as they did not hold a citizen’s rights or the right to own property. Nevertheless, they could through matrimony connect families and give birth, so they were considered valuable.2Allan, W. (ed) 2008. Euripides: Helen, p. 50, 52 If they also happened to be attractive, they held “power” over influential political men and thus threatened the prosperity and balance of society. In other words, since they did not play any political or economic role in the public sphere, their “influence” over men ought to be controlled lest there be an accident. It is therefore not unreasonable that the “nature” of women was discussed so extensively in ancient Greece, especially since it simultaneously defined the position and obligations of men. Because, while the name of the play may be “Helen”, the authors – Sappho excluded – were always men, the theatre audience was overwhelmingly male, and political and social power was certainly in the hands of a minority of men.

CHAPTER 3 / HELEN BY EURIPIDES

Within this social context, many ancient Greek poets and philosophers explored the idea of “Helen”, the idea of the moral and physical influence of the female sex in their society.

Similarly, they explored other cases (and situations): they created Antigone, Clytemnestra, Orestes, Bacchae, Agamemnon, and Frogs in order to address on stage various issues that concerned them and to account for factors such as “fate”, “destiny”, “morality”, and “justice” in human life. Homer’s “Helen of Troy”, the one who was kidnapped and was the “cause” of the Trojan War, was the first “Helen” to acquire such importance in the mythical tradition and from then on poor “Helen” became synonymous with destruction throughout antiquity.

The Embarkation of Helen of Troy by Jacopo Amigoni, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

At school, for example, we learned about Euripides’s Helen. Euripides was so interested in the study of the female gender that Aristophanes commented on the fact in his own comedies. Thirteen out of the nineteen surviving plays by Euripides feature women as their protagonists; their themes often revolve around the relationship between the sexes in society, and his heroines share their gendered experience on stage, expressing what it feels like to live as a woman in society.3Blondel, R., Gamel, M-K, Rabinowitz, N. S, Zweig, B. (Trans and ed.) 1999. Women on the Edge: Four Plays by Euripides (Alcestis, Medea, Helen, Iphigenia at Aulis), pp.80-81Different versions of tragic heroines are found throughout the history of opera, like for example Lucia di Lammermoor in Gaetano Donizetti’s work of the same title (pictured below).

Highlights of the opera Lucia di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti, from the co-production of the Greek National Opera with the Royal Opera House of London. Conductor: Pierre Dumoussaud/Lukas Karytinos, stage direction: Katie Mitchell, staging revival: Robin Tebbutt, set and costume design: Vicki Mortimer, Stavros Niarchos Hall, 2019

Highlights of the opera Lucia di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti, from the co-production of the Greek National Opera with the Royal Opera House of London. Conductor: Pierre Dumoussaud/Lukas Karytinos, stage direction: Katie Mitchell, staging revival: Robin Tebbutt, set and costume design: Vicki Mortimer, Stavros Niarchos Hall, 2019

Although friendlier than other versions that condemn “Helen” as a force destructive to her society, even Euripides’s tragedy cannot be considered radical in its treatment of the female gender. “Helen” may be presented as a victim of circumstance but the tragedy did in no way seek to critique the hegemony of male thought and behavior, or the poetic tradition that associated womanhood with destruction. So “Helen” here too remained bound by her “nature”: a beautiful and– at least inadvertently– destructive woman who ought be controlled by her husband.4Allan, W. (ed) 2008. Euripides: Helen, p. 55

CHAPTER 4 / “HELEN” IN PARIS

So what makes this devilishly beautiful “Helen” appear on the French operatic stage in 1864? Certainly not some moral or political quest on the part of its creators.

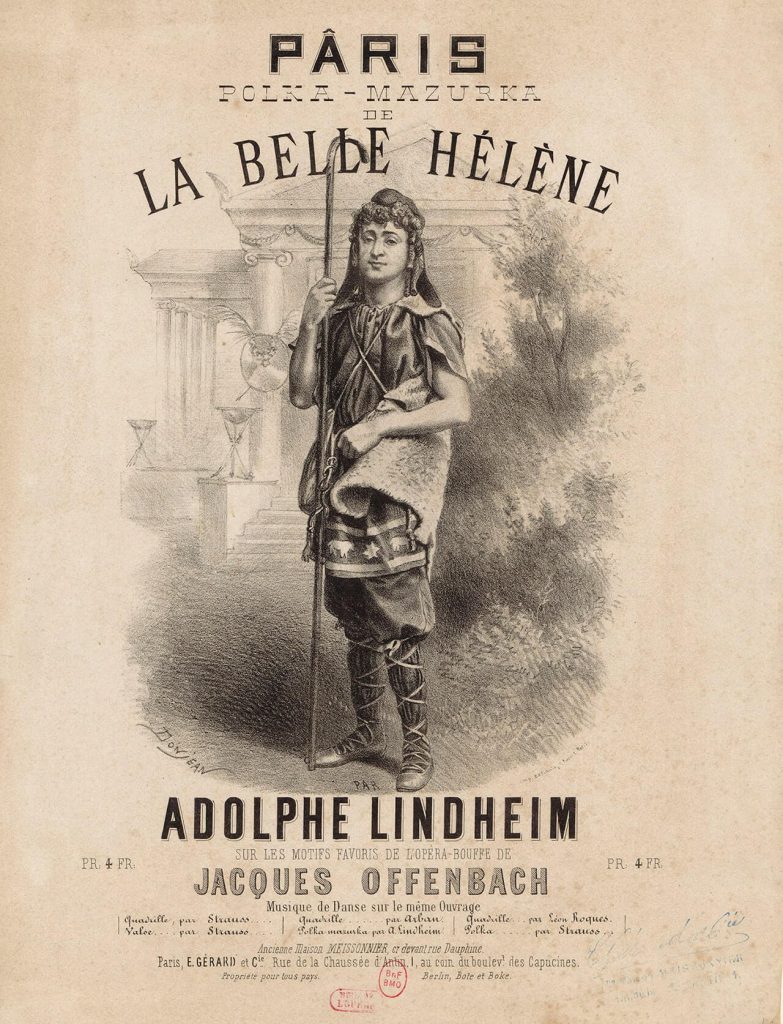

19th century music score with popular extracts from La Belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach, Gustave Donjean, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When German composer Jacques Offenbach began his career in Paris, Emperor Napoleon III exercised absolute control over theatrical production in order to prevent the dissemination of revolutionary ideas.5The cambridge companion to operetta, p. 73 [pdf] Thus Offenbach introduced and built his career on the genre we call operetta, a genre that provided musical entertainment, avoided political commentary and is considered the forerunner of today’s musical. And Offenbach excelled at it. Not only did he write 100 pieces of music theatre during his career, but he also founded a very successful theatre in Paris. After the success of his Orphée aux enfers, he decided to stage a version of the myth of Helen in 1864, as ancient Greek themes were popular in Paris at the time. And thus La Belle Hélène was born, a comic operetta so popular that it was performed 700 times in Paris and travelled throughout Europe and the USA over the next six years. The theme of this “Helen” may appear to be connected to ancient Greece, but as is often the case in art, behind the costumes, plot and characters of antiquity, Offenbach concealed a musical parody on the endless thirst of Parisians for spectacles and entertainment.6ibid. 83

Caricature of the operetta La Belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach (1864), source: Europeana.

Archive material from the Greek National Opera production of La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach. Conductor: Walter Pfeffer, stage direction: Frixos Theologides, set and costume design: Lisa Zaimi, Olympia Theatre, 1960/61

Archive material from the Greek National Opera production of La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach. Conductor: Walter Pfeffer, stage direction: Frixos Theologides, set and costume design: Lisa Zaimi, Olympia Theatre, 1960/61

Highlight from the operetta La vie parisienne by Jacques Offenbach. Conductor: Andreas Pylarinos, Lisa Xanthopoulou, stage direction: Yannis Iordanidis, set and costume design: Giorgos Patsas, Olympia Theatre, 2003/04

CHAPTER 5 / “HELEN” BY KORNILIOS SELAMSIS

The modern version of “Helen”, which you will watch from the Greek National Opera, is a combination of all of the above elements, as the performers will explain.

Using fragments of Offenbach’s music, Offenbach’s “La belle Hélène” by Kornilios Selamsis and librettist Alexandra K* takes this troubled ancient heroine and lends her a satirical voice in Greek reality. Pay attention to the libretto to hear comments and opinions about our society, thoughts on our culture and the place of women in it, and of course don’t forget to write to me after the end of the performance to let me know if “Helen” in this version is a woman who has no say over her fate. Traditions are always subject to change and you might be surprised.

In the following link you can take a look at the programme of the performance and browse through the story of Helen through the notes of its creators. https://www.nationalopera.gr/images/flipping/programma/en/

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

Soloists Maria Tsironi and Smaragda Vaggeli in the role of “Helen” in the performance La belle Hélène by Jacques Offenbach and Kornilios Selamsis. Conductor: Stathis Soulis/Kyriaki Kountouri, stage direction: Yannis Kalavrianos, set and costume design: Petros Toloudis

QUIZ / THE BEAUTIFUL HELEN

ACTIVITIES / THE BEAUTIFUL HELEN

Introduction

Imagine that you take on the role of the costume designer in the opera La belle Hélène of Offenbach by Kornilios Selamsis. After your first meeting with the artistic team, you are asked to prepare a presentation for your next meeting. After having studied the story of La belle Hélène, as intended to be set in this opera, can you imagine and create a costume profile for your own “Helen”?

Connection to the curriculum

– Art class

– Ancient Greek

Subjects

Suggested teaching hours

Educational objectives

– Familiarizing with the trans-artistic nature of opera

– Cultivating imagination

– Exploring creativity

– Developing critical thinking

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

Step 1

Below you will find a brief description of the opera La belle Hélène by Offenbach. Before you explore how you would like to dress your own “Helen”, you should be very familiar with her story. Read the description carefully and discuss any possible questions or thoughts in class.

Brief description of the story

The story takes place in two locations (acts 1 & 2 in Sparta and act 3 in Nafplion, in a seaside resort). The time of the story is set in the summer before the beginning of the Trojan War.

In the market of Sparta where all heroes are gathered, Paris appears disguised as a shepherd, with the aim of taking part in the Spirit Games of Sparta and claiming the Beautiful Helen. Paris, who has been spotted by the oracle Calchas and Helen, wins the Spirit Games. A month later, and while the oracle Calchas, at Zeus’ command, sends Menelaus to Crete, Helen, in the midst of reality and dream, comes closer to Paris. Menelaos surprises Helen by returning early from Crete and accusing her of infidelity. A week later all the heroes are taken to Nafplion (a summer resort), the tension between Helen and Menelaos continues, while Agamemnon and the oracle Calchas, knowing the development of the myth, try to convince Menelaos to let Helen go. A ship arriving in Nafplion brings the upheaval. The ship arrives at the port and Paris appears, this time disguised as the Grand Oracle of Aphrodite. Everyone greets him with joy and respect, while Helen realizes who he really is. Wanting to satisfy the request of the goddess Aphrodite, the Seer asks to take Helen with him to Cythera, at the side of the goddess. The story ends with Helen leaving with Paris (the Great Oracle), wanting to satisfy the Goddess’s request. Before she leaves Nafplion, however, she warns Menelaus and Agamemnon that her fleeing to Troy cannot be a reason for the war to begin as she was not taken by Paris by force, but it was her own desire to follow him.

Step 2

For this particular activity you can work individually or in small groups

1. Pick five adjectives that describe the character of Helen and make a note of them.

2. Describe the physical appearance of Helen, as you imagine her, in a short paragraph.

Step 3

Share the different descriptions and adjectives and discuss the similarities and differences between the ‘Helens’ in your class.

Do your descriptions remind you of another heroine from history, comics or film?

Step 4

Based on the aforementioned step, and thinking about the profile that you would like your own Helen to have, find images on the internet and create a collage with them, which will serve as a reference for your sartorial perspective in this particular production.

With the story of Offenbach’s La belle Hélène in mind, and everything you have discussed and thought about, you can try to create a “map” for your image of Helen using the moodboard. Newspaper and magazine clippings, pictures, artwork, photos and sketches from the internet, photos and our own sketches, colour palettes, pieces of fabric and other materials, short texts-ideas and anything else you can imagine can create the collage on the moodboard.

Attention! We should not necessarily be limited by the fact that the original story of Helen is set in ancient Greece. In opera and theatre we can often watch an ancient tragedy with futuristic costumes and a Don Giovanni who, instead of a white-bottle wig and waistcoat, wears colourful bell-bottom trousers, a light floral shirt and sunglasses. Unleash your creativity and create the “Helen” you would like to see on stage.

Step 5

Based on the moodboard you created in step 4 now draw a sketch of your own “Helen”.