Opera

in Greece

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

The third chapter explores and presents to you the evolution of opera as a genre in Greece, from its arrival in the Greek territory to this date. A journey that begins from the Teatro di San Giacomo on Corfu and stretches all the way to the Greek National Opera. In the following video, Panaghis Pagoulatos, the Director of Artistic

Coordination & Casting of the Greek National Opera, presents an overview of the history of the genre of opera throughout Greece.

Panaghis Pagoulatos, Director of Artistic Coordination & Casting of the Greek National Opera, presents an overview of the history of the genre of opera throughout Greece.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / OPERA IN GREECE AND THE GREEK-SPEAKING TERRITORIES

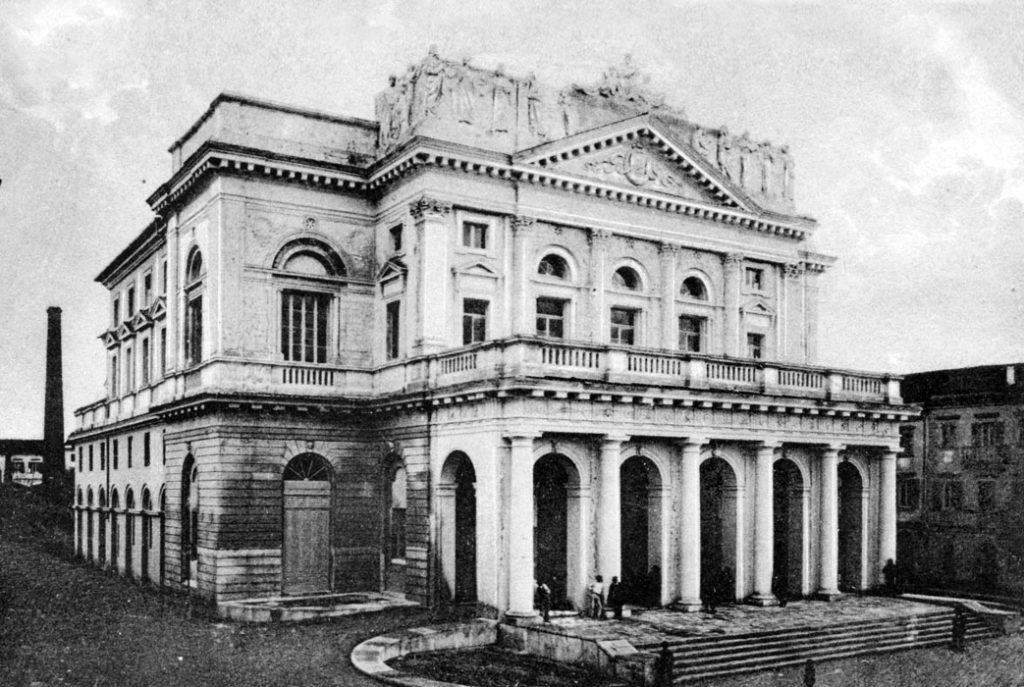

The Municipal Theatre of Corfu, 1903 (Ε. Fessa-Emmanouil: Modern Greek theatre architecture.)

At last it’s time to talk about opera in Greece! Until now we toured around the operatic worlds of Italy, Germany, and France; we discussed early opera, court musicians, and chess playing during opera performances. After these journeys through the various histories of opera, we decided to dedicate a special little corner to explore how and when opera became part of Greek musical tradition. The most straightforward answer to the question of the introduction of opera in Greece (or the Greek-speaking territories more broadly) is that composers from the Greek community of the Ionian Islands wrote operas long before the Greek state was even created. The ‘San Giacomo’ theatre on the island of Corfu, for example, ran a regular operatic season since 1771, while in 1791 the Ionian-Greek composer Stefano Pogiago presented his opera Gli amanti confusi.

Have you ever listened to a Greek opera or an opera by a Greek composer?

The Swedish soprano Johanna Maria “Jenny” Lind in the role of Lucia di Lammermmor at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London (Illustrated London News, 1848)

As for the Greek state, where our main story takes place, things were somewhat more complex. As you may already know from your school history lessons, in 1833 the Great Powers supported the ascension of the Bavarian prince Otto Friedrich Ludwig von Bayern to the Greek throne. The following year, the capital of the new Kingdom of Greece was transferred to Athens and here’s where trouble began for Otto and his new court. Because, while the Parthenon is very pretty, Athens at the time was but a small town that lacked most of the comforts a King and Queen might have expected to enjoy in a modern European capital. And so, to cure Queen Amalia’s evening boredom in a city that did not present her preferred evening entertainment, the Royal couple ordered and partly financed the construction of a theatre. In 1840 the Theatre of Athens opened its doors with a production of Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermoor.

CHAPTER 3 / POPULAR GREEK ENTERTAINMENT

Therefore, opera in Athens became a regular form of entertainment mainly because of the intervention and financial support of the Palace.

However, the limited financial capabilities of the Greek state in combination with the equally limited financial capabilities of the Greek throne throughout the 19th century meant that opera in Athens received significant financial support by private theatre investors, the local dignitaries and the middle class of the city– who purchased seasonal tickets for seats or theatre boxes.25Κ. Σαμπάνης 2014, Η όπερα στην Αθήνα κατά την οθωνική περίοδο (1833-1862) μέσα από τα δημοσιεύματα του τύπου και τους περιηγητές της εποχής, σ. 104-109. And so even though opera was not the preferred form of entertainment for the majority of the citizens of Athens, the military band of the city performed popular melodies from the opera every Sunday in public spaces, gradually making it familiar to increasing numbers of people.26Κ. Σαμπάνης 2014, σ. 133. Ticket prices, on the other hand, remained too expensive for citizens who did not belong to the privileged classes and so for this and other reasons the majority of Athenians continued enjoying variety shows with contortionists or folk shadow puppet theatre (Karaghiozis).27Α. Σκανδάλη 2001, Η πορεία της όπερας στην Ελλάδα του 19ου αιώνα σε σχέση με τη συγκρότηση του αστικού χώρου, σ. 56-57.

Karaghiozis shadow-theatre puppet photos, Folklife & Ethnological Museum of Macedonia-Thrace.

As you can imagine, this fundamental division in the preferred entertainment of the different classes became the reason for great debates in Athens. Imagine living in a city and a country where the majority of the people enjoy listening to folk music and shows of shadow puppet theatre, while the government invests its little money in financing Italian opera. And how many people understood Italian at the time, anyway? One side said that the Greeks were a people with an Eastern and Christian cultural heritage and therefore they ought to be educated in Byzantine chant; the other side said that the Greeks were in the process of affiliating culturally with the West and so they ought to become familiar with Western music. Others said that, as beautiful as opera may be, perhaps the state’s priority ought to have been instituting a national theatre, training Greek actors and producing Greek plays. The truth of the matter is that Greece at the time was a new country with a lot of needs and little available money, and the ruling classes of Athens prioritised Italian opera. During the rest of the 19th century a number of other cities with a prospering middle or commercial class supported the institution of theatres that presented theatre and opera. In 1864 the impressive ‘Apollon Theatre’ opened its doors on the island of Syros in the Cyclades, in 1872 the city of Patras in the Peloponnese opened its own ‘Apollon Theatre’, while in 1895 the ‘Theatre of Pireaus’ was instituted in the city of Piraeus.

View of the auditorium and the main stage of the ‘Apollon Theatre’ in Syros from the upper balcony, animasyros7 (2014), Fotismar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

CHAPTER 4 / A NEW SOURCE OF EMPLOYMENT

Amidst the debates mentioned above, the Theatre of Athens was finally instituted in 1840 to become the first state-financed theatre running regular operatic seasons. As such the Queen’s evening boredom may have decreased significantly while disagreements increased proportionately, but at the same time the theatre became a new employer for musicians

As we already saw at the beginning of this section, Ionian-Greek musicians participated in the tradition of Italian opera long before opera came to Athens– remember, the Ionian Islands remained under British administration until 1864. And what happens when a brand new theatre opens in a neighbouring country that shares the same language? There are new professional opportunities on offer! Since Greece did not yet have music schools or enough professional musicians to run regular operatic seasons, orchestra players and singers were recruited through Italian artistic agencies. With time some of them found stable jobs in Athens, while at the same time Ionian musicians and composers began working regularly in Greece and writing Greek operas. In 1858, for example, Ionian-Greek composer Pavlos Carrer composed the opera Marco Bozzari,– originally set to an Italian libretto and translated into Greek shortly after– as well as Kyra Frosini and Despo later on. The first opera to be set originally to a Greek libretto– and more importantly using everyday Greek– was The Parliamentary Candidate by Ionian-Greek composer Spyridon Xyndas, and its premier in 1888 Athens marked an significant milestone for the history of opera in Greece. It is also important to note here that Ionian-Greek composers established successful careers outside the small Greek operatic market. Spyridon (Spyros) Filiskos Samaras’s operas Flora Mirabilis (1866) and La Martire (1894) were popular in Italy, while composer Napoleon Lambelet worked in London’s West End for some years.28Φ. Ανωγειανάκης 1958, «Η μουσική στη νεώτερη Ελλάδα», επίμετρο στο: Καρλ Νεφ 1956, Ιστορία της μουσικής, σ. 565· Μ. Σειραγάκης 2014, Ναπολέων Λαμπελέτ: Ένας ανέστιος κοσμοπολίτης, Αθήνα: Κέντρο Ελληνικής Μουσικής.

Excerpt from Pavlos Carrer’s Despo, in musical direction by Giorgos Ziavras and stage direction by Giorgos Nanouris (2006/07). A GNO production for the bicentenary of the Greek Revolution.

Excerpt from the first production of Spyros Samaras’ Flora Mirabilis in Olympia Theatre, in stage direction by Giorgos Michailidis (April 1979)

In 1871 a new opera-related trend became popular in Athens. In preparation for the visit of King George I’s family from Denmark, the Greek government invited a French opera company to perform Jacques Offenbach’s operetta La vie Parisienne.29A. Xepapadakou, «Operetta in Greece», στο: A. Belina – D. Scott (επιμ.) 2020, The Cambridge Companion to Operetta, σ. And while the conservative press reacted negatively and often attacked operetta as harmful for the moral edification of Greek youth, the genre became an instant success with Greek audiences. The first attempt for an operetta in Greek was Pavlos Carrer’s Count Sparrow in 1886, but the work remained unpublished and the original score has been lost.30Ό.π., σ. The most well-known Greek composer of operetta today is Theophrastos Sakellaridis, who also wrote music for revues, and whose operetta The Godson remains popular with Greek audiences. Moreover, songs from Sakellaridis’s operettas entered popular culture and continue to be enjoyed beyond the theatre. If you know a Greek person ask them and maybe their parents or grandparents can sing one for you!

Excerpt from Theophrastos Sakellaridis’s operetta Sataneri, in music direction by Charalambos Giogios, and stage direction by Alexandros Efklidis and Dimitris Dimopoulos. Alternative Stage of the GNO (2018/19)

Are you familiar with other examples of Greek music that has elements from ‘foreign’ styles or the other way around?

CHAPTER 5 / OPERA ‘INTEGRATED’ TO GREEK CULTURE

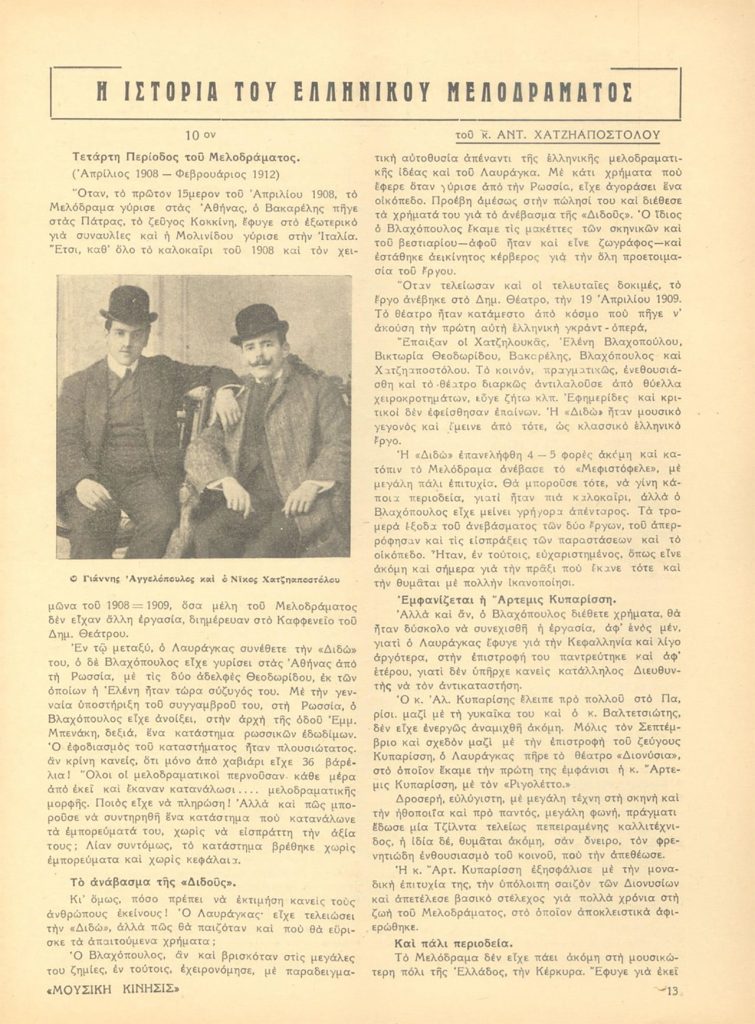

The warm reception of the Parliamentary Candidate by the Athenian audience in 1888 became the catalyst for the establishment of the first two opera companies that trained Greek singers and produced operas in the Greek language. The “Greek Opera Troupe” (1888-1890), established by singer Antonios Landis and financed by Ioannis Karagiannis and later on the “Greek Opera [company]” (1900-1943) led by composer and conductor Dionysios Lavrangas and conductor Loudovikos Spinellis, contributed actively to the development of this neglected aspect of Greek opera production. Both opera companies focused on making opera accessible by producing works in the Greek language, they presented Greek operas outside Greece, and they trained Greek singers.31Κ. Καρδάμης – Α. Ξεπαπαδάκου 2017, Ο Υποψήφιος, επετειακή έκδοση (1867-2017), σ. xliv. Thus opera, a spectacle that had been until then performed mainly in foreign languages and by non-Greek singers, found its place among the other genres of Greek music.

Article on the history of Greek opera from the music journal ‘Mousiki Kinisis’, 1950, source: Europeana.

Watch the following excerpt without subtitles and guess its topic, as well as the emotions it evokes. Then, turn on the subtitles. Does the music feel different after knowing the lyrics?

Excerpt from the aria “E lucevan le stelle”, from Giacomo Puccini’s opera Tosca. Soloist: Jonas Kaufmann, Odeon of Herodes Atticus theatre, 2021.

Can we enjoy a song even without understanding its lyrics?

As for the Greek state, which subsidized the production of opera from very early in its inception but never prioritized singer training during the 19th century, it finally took action in 1939. Initially instituted as part of the Royal (National) Theatre, and under the direction of Kostis Bastias, this first state initiative to support art song in Greece presented a number of operettas.

The first singers of the Royal Theatre with Kostis Bastias, the first Director of the opera company at the centre (1939), photo from the GNO archive.

The choir of the National Opera of the Royal Theatre, Athens 1939, photo from the GNO archive.

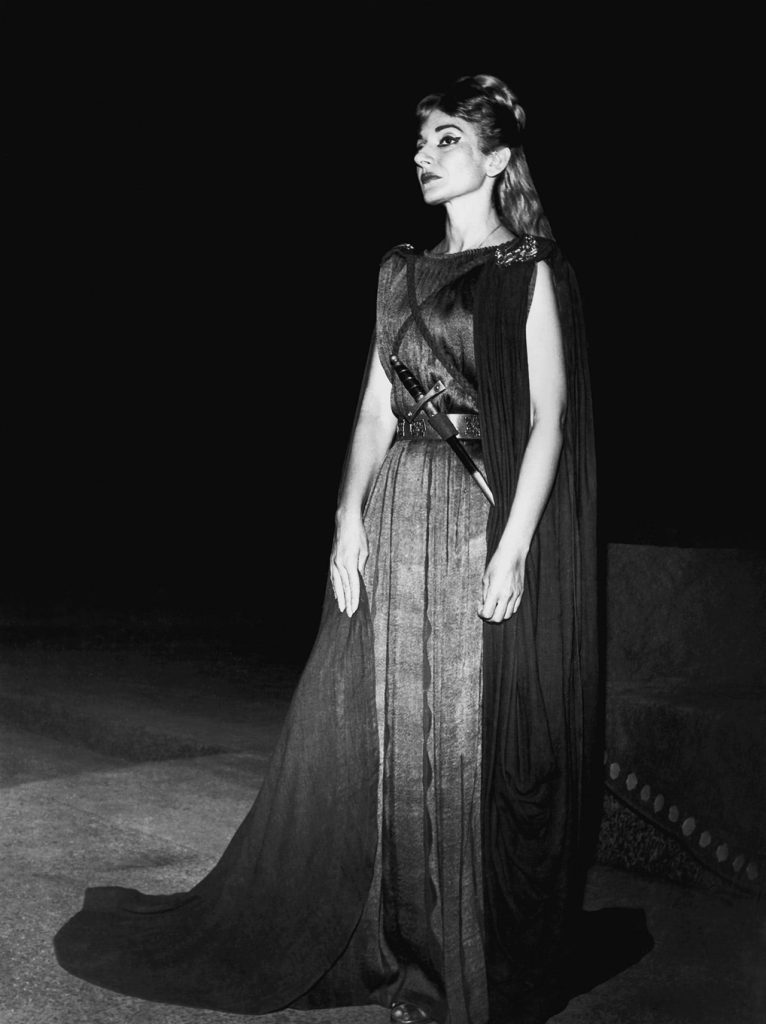

Among the most significant early achievements of the new organization was the recognition of the talent of the then fourteen year-old Maria Kalogeropoulou – later Callas –, whom Kostis Bastias personally hired as a member of the choir in order to assist her secure an income until the completion of her musical training.

The world-renowned Greek soprano Maria Callas (1923-1977) – Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, Norma, 1960, photo from the GNO archive.

The Greek National Opera in its current form became an independent institution specializing in opera in 1944 and opened its doors with a production of the opera Rhea by Spyros Samaras, under the musical direction of Manolis Kalomiris.32Κ. Ρωμανού 2006, Έντεχνη ελληνική μουσική στους νεότερους χρόνους, σ. 225.

Throughout the 20th century Greek artists continued writing music for the genre of opera, even thought the production of new works remained small and limited to Athens. Manolis Kalomiris, for example, composed The Masterbuilder, The Mother’s Ring, and Konstantinos Paleologos. Dionysios Lavrangas composed Black Butterfly and The Saviour, while in 1945 Marios Varvoglis composed his only completed opera, The Afternoon of Love. The genre of operetta became particularly popular during the same period, with composers Nikos Chatziapostolou and Theophrastos Sakellaridis producing many of their most popular works.

As you may have noticed in the list above, opera production appears to have accelerated since 1990. In the past few years this renewed interest has been supported by a series of commissions of new works by the Greek National Opera.

Minas Borboudakis, Ζ, Greek National Opera commission, Alternative Stage of the GNO (2017/18).

Excerpts from the opera Medea by Nikos Kypourgos, conductor: Elias Voudouris, stage direction: Giannis Skourletis / bijoux de kant. A Greek National Opera commission, Stavros Niarchos Hall, 2018/19

Excerpt from the opera ANDREI by Dimitra Trypani. A Greek National Opera commission, Stavros Niarchos Hall, 2022/23

George Koumendakis, The Murdress, conductor: Vasilis Christopoulos, stage direction Alexandros Efklidis, Stavros Niarchos Hall, GNO (2021/22).

Have you ever seen or listened to any of the aforementioned Greek operas?

Opera was ‘imported’ into Greece as a form of entertainment favoured by a small minority. Some supported it to cure their evening boredom, others because they felt more’ European’ because of it; some went to the opera because others went as well, and a few went because they were genuinely enchanted by the genre. Whether for reasons of personal, artistic, or national identity, composers and audiences formed a bond with the genre, some led important careers in it and were placed in important state positions, while others were forgotten. Opera production is contingent on the hard work of highly trained and specialised workers, in a variety of fields: composers, librettists, conductors, stage directors, stage designers, costume designers, lighting designers, musicians, scenery constructors, singers, voice coaches, acting coaches, dialect coaches, dancers, and animal trainers. It requires the existence of effective educational institutions for musicians of all levels and specializations. It demands artistic commitment, time, meritocratic selection procedures, and long-term financial policies by state and private bodies. Above all it needs our active participation as an audience that thinks about the genre critically, and demands each new work to be at least as good as the best opera work ever staged.

Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini. Conductor: Vassilis Christopoulos, stage direction: Olivier Py, sets and costumes: Pierre-André Weitz, Odeon of Herodes Atticus (2023), photo by Haris Akriviadis

QUIZ / OPERA IN GREECE

ACTIVITIES / OPERA IN GREECE

Introduction

Connection to the curriculum

– Modern Greek

– Music class

Main themes

– Producing an idea

– Libretto

– Literature and music

Suggested duration

2 teaching hours

Educational objectives

– Understanding of and developing connections between speech and music

– Research skills

– Development of imagination

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

Giorgos Koumendakis, current Artistic Director of the Greek National Opera, is one of the most important Cretan composers of his generation, and has also composed works for the opera. His four operas have all been staged, while the GNO commissioned the most important among them – The Murderess. Koumendakis’s Murderess, in a libretto by Giannis Svolos, was completed in 2014 and is based on Alexandros Papadiamantis’s titular novelette, which Greek students study as part of their Modern Greek Literature module in year 11.

In the following activity we will explore the relationship between a literary work and the production of a new opera. Then we will create a mind map in order to trace those aspects that we chose to use in our own original opera work.

Step 1

Watch Giorgos Koumendakis discussing his opera in the short video below:

Giorgos Koumendakis, Artistic Director of the Greek National Opera and composer of the opera The Murderess, discusses about his approach to the novel of Alexandros Papadiamantis.

After watching the video in the classroom you may discuss the following questions:

– What was the composer’s approach to the heroine of the original text?

– Where did he draw inspiration from?

– Did the composer focus more on the characters of the novelette or on the general setting of the work?

You may find the original novelette by Alexandros Papadiamantis, in Greek, in the link below:

Step 2

Imagine yourself as a member of a team creating an opera or a piece of musical theatre based on a literary text. Research through various pieces of literature and select one to create your own libretto.

Step 3

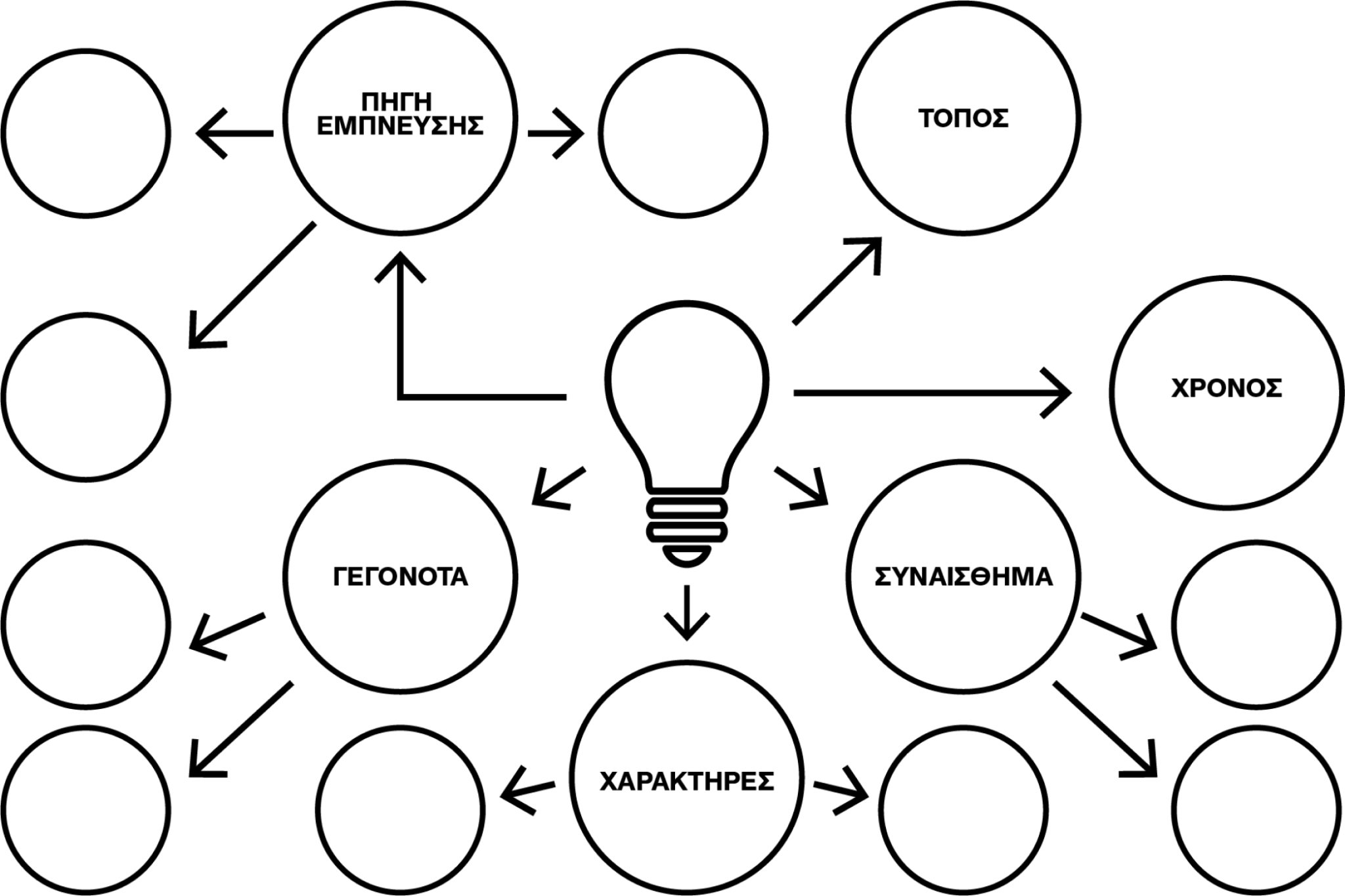

After selecting and analysing you text, create a mind map* containing all of your ideas about it and about your opera project, keeping in mind the following questions:

1. Which aspects of the text were the most inspiring and could be used as a starting point for your opera?

2. Which emotions did the text evoke?

3. Which elements of the story were of central importance to its development and how do they connect to other events or elements in the storyline?

4. How can your text be connected to the present? Are there elements that we can still observe in our society and everyday life?

* mind–map: a mind map is an organisational tool that helps us structure our thoughts – or our team’s thoughts- around a topic of interest.

See the following mind-map as an example: