The birth

of opera

CHAPTER 1 / INTRODUCTION

In the chapter The birth of opera you will find all the information that will help you understand how opera emerged as a new genre, what the sources of inspiration of the first opera composers were, and how the genre has developed from its origins to its arrival at prestigious opera houses. In the video you will find below, composer Kornilios Selamsis and librettist Alexandra K* discuss about the birth of the genre and the distinctive element of the ancient Greek myths that inspired the first opera composers.

Composer Kornilios Selamsis and librettist Alexandra K* discuss about the birth of the genre and the distinctive element of the ancient Greek myths that inspired the first opera composers.

The following texts are written by Artemis Ignatidou.

CHAPTER 2 / THE BEGINNING OF OPERA: A MUSICAL EXPERIMENT

As is often the case in the sciences and the arts, opera was invented as a musical experiment on older ideas.

Specifically, between 1573 and 1587, in Florence in present-day Italy, a group of noblemen and musicians started discussing the relationship between speech, music and science. Through their musical and theoretical experiments this group, which we call Camerata, intended to revive the music that accompanied ancient Greek drama, which had been preserved only in written descriptions until then.1Sadie, St (ed) 1988. The Grove Concise Dictionary of Music, p. 127; Arnold, D (ed) 1983, The New Oxford Companion to Music, vol 2, p. 1291 Thus, using popular Italian musical genres of their time as well as their own theories on the theatre and music of antiquity, they created the musical dramas that introduced the genre of opera: Dafne (1598) and Euridice (1600).

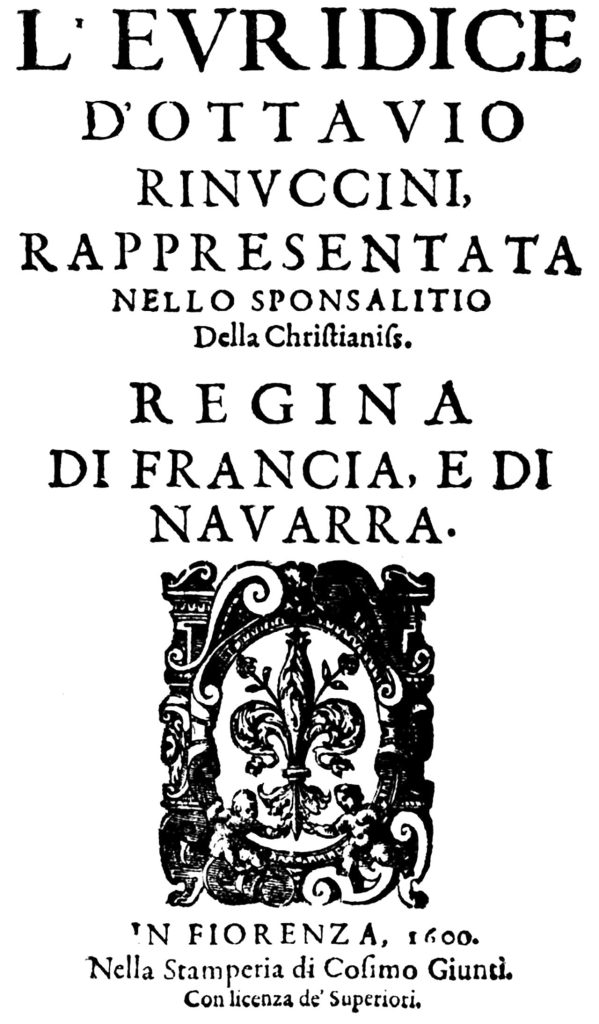

Title page of the libretto of Ottavio Rinnuccini for the opera Euridice (1600) by Jacopo Peri, Ottavio Rinuccini, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The historical reasons for this artistic initiative of Camerata are complex. However, to put it simply, we could say that it was the result of the political structure of governance in Florence, a significant historical event that created an emigration wave, and the general tendency of the arts to reinvent themselves by reusing older popular ideas and theories.

The historical event was no other than the conquest of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire, by the Ottomans in 1453. You are probably now wondering; the musical experiment by Camerata took place 120 years later than the conquest of Constantinople, how could they be related? And what sort of experiment takes that long to be experimented upon? Here comes the second historical reason, which was the migration wave caused by the conquest of Constantinople. Just like today, when war forces people to flee their homes, the conquest of Constantinople pushed a significant number of Byzantine – Greek scholars to seek safety in other parts of Europe. And like the refugees that arrive now bring with them, not only their belongings, but also their skills and knowledge, so did the scholarly immigrants of so many years ago, bring with them texts from their libraries, as well as their own knowledge.2Arnold, D (ed) 1983, The New Oxford Companion to Music, vol 2, p. 703

The Bosporus and the entrance to the Black Sea (1819), source: Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

These texts were ancient Greek and Roman writings, as well as theatrical dramas, which inspired Western Europeans, such as the members of Camerata, to model their societies after the moral and cultural teachings of these ancient civilisations. And while today these ideas might be posted on social media and spread immediately, ideas at the time of Camerata spread through books, the arts, warfare, and debates in palaces, universities, churches, and intellectual circles such as Camerata itself. Artists, monarchs, noblemen and philosophers, further interpreted these Greek and Roman texts and created or funded works of art, during the period we conventionally call the ‘Italian Renaissance’.

In music, drawing on medieval music theory and ancient Greek treatises, the music historian and theorist Girolamo Mei argued that ancient poets highlighted the beauty of their text by writing the musical parts of ancient Greek drama in a ‘monophonic’ style.3Haar, J. ‘The Concept of the Renaissance’ in Haar, J. (ed) 2006. European music 1520- 1642, pp. 25-29 ; Gerbino, G, Fenlon, I. ‘Early Opera: the initial phase’ in ibid. p. 474 Based on this theory and the musical culture of their time, Camerata members Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini composed the first musical dramas.

Jacopo Peri in costume at the performance of La Pellegrina (1589), Bernardo Buontalenti (c. 1531 – 1608), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Can you find other connections between historical events and artistic trends?

CHAPTER 3 / CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI

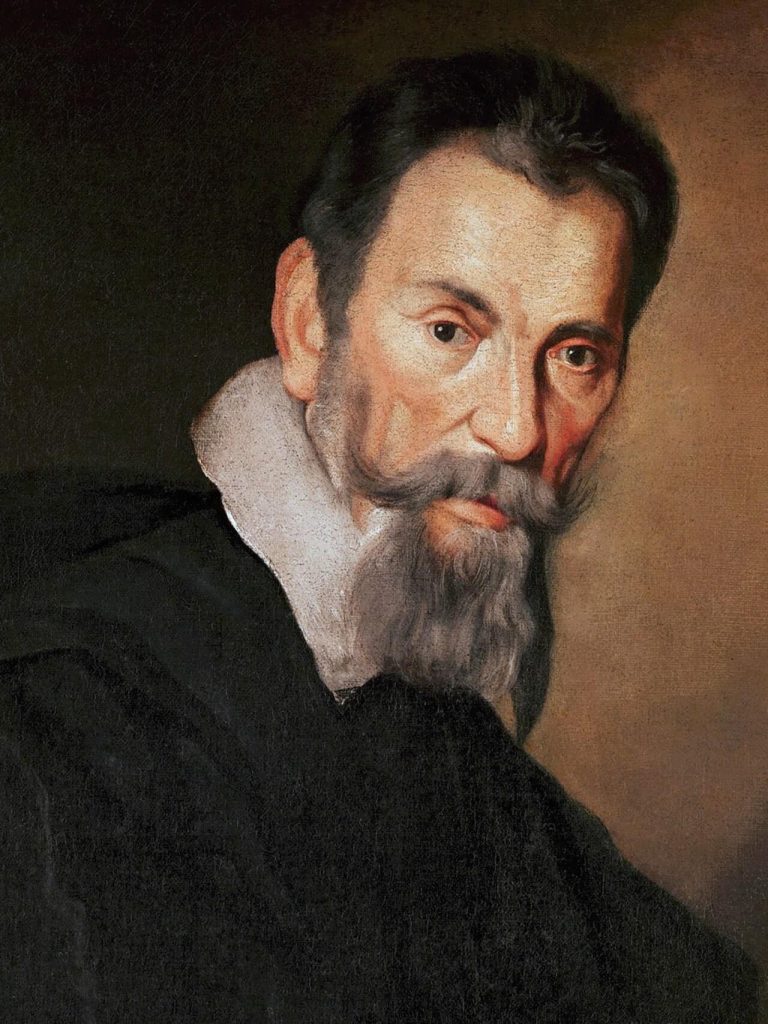

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), Bernardo Strozzi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Part of these interpretations of the ancient texts that were created during the ‘Renaissance’ can also be found in the operas of the time, which we enjoy both for their musical and literary value as well as for the historical information they provide.

For example, let’s look at Claudio Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo (1607), which is one of the earliest surviving musical dramas as the music of the first opera Dafne has survived only in parts. L’Orfeo was composed when the Duke of Mantua attended Peri’s musical pastoral drama Euridice in Florence and commissioned Monteverdi, head musician of his own court, to compose an opera on the same theme.4Ch. Osborne 2004, The Opera Lover’s Companion, σ. 238. Therefore, L’Orfeo may not have been the first opera ever composed, but it is considered the first opera to be included in the repertoire for its artistic rather than its historical value.5Arnold, D (ed) 1983, The New Oxford Companion to Music, vol 2, p. 1292 Monteverdi, a talented composer of madrigals and sacred music, drew inspiration from the musical dramas of Peri and Caccini and introduced a series of novelties that proved significant for the development of baroque opera. Contrary to earlier works, where a few lutes and a harpsichord accompanied the singers from backstage, Monteverdi used an orchestra of 40 instruments, including a wide variety of continuo instruments, he composed 26 short movements of exclusively orchestral music and he included duets, dances and arias for solo instruments. The librettist Alessandro Striggio, in his turn, transformed Ottavio Rinuccini’s short pastoral drama into a five-act drama.6Grout, D. J, Pelisca, C. V (eds) 1996 (5th ed) A history of Western music, p. 284

L’Orfeo reflects not only the musical innovations of its time but also part of the society for which it was composed. As you will have noticed, Monteverdi was a court musician, that is, a servant of the Duke. Secondly, until recently in history the vast majority of composers were strictly male, as composition was considered an exclusively male talent. Finally, even Striggio’s libretto gives us information about the evolution of ancient Greek thought throughout the centuries: from the original pagan Orphic myth, through the Roman versions of Virgil and Ovid, to its Christian Renaissance form, and finally to us. Opera, therefore, can be understood as a living narration of how we humans understand and interpret our existence in time and in our society. It also reflects how we perceive our past and our history, and the demands we voice about our present and our future.

ORFEAS2021, a video-opera by FYTA based on Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (a Greek National Opera production)

What do you think of the coexistence of these different elements?

CHAPTER 4 / FROM THE COURT TO PUBLIC THEATRES

Back to the Renaissance and its rapid developments for now… Despite the initial interest of the Florentine court for musical pastoral dramas, and some operas composed for the Papal Court in Rome, the aristocracy continued to prefer ballet as their main form of entertainment.

As a result, only a few musical dramas were composed over the next 30 years. Monteverdi composed just two more operas in this period – Arianna (1608) and Licori finta pazza (1627). Apart from the musical dramas already mentioned, the operas La Dafne (1608) and Il Medoro (1619) were composed by Marco da Gagliano, as well as the opera La Flora (1628) by Gagliano and Peri.7ibid. p. 287; Arnold, D (ed) 1983, The New Oxford Companion to Music, vol 2, p. 1292

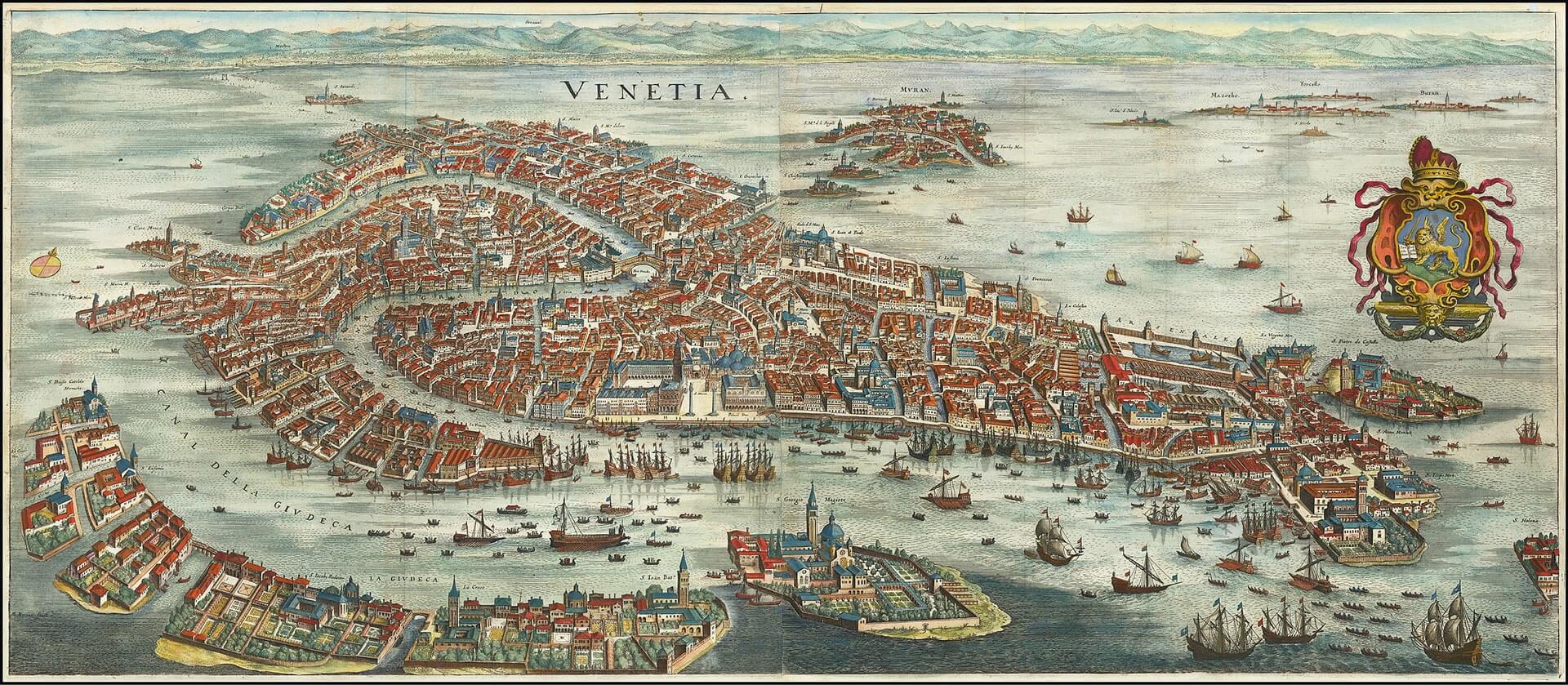

The next major turning point in the history of opera seemed again to be long in coming. And yet, when the Teatro San Cassiano opened in Venice in 1637, the course of opera changed forever. Because, while you could justifiably assume that it is the content of an artwork that matters rather than the space where it is presented, it was the performance of opera to a wider, more diverse audience, in a public theatre, which gave it the outlook we recognize until today.

Venice in 1636 as rendered by Matthäus Merian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

L’incoronazione di Poppea by Claudio Monteverdi in a production by the Greek National Opera (Olympia Theatre, 1977/78)

L’incoronazione di Poppea by Claudio Monteverdi in a production by the Greek National Opera (Olympia Theatre, 1977/78)

Plotlines began to reflect issues that concerned a larger part of society, composers started adapting their music to the audience’s preferences, and productions responded to the audience’s thirst for impressive technological spectacles on stage.8Palisca, C. V. 2006. Music and Ideas in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries, pp. 127-128 In addition, more professional opportunities were created for composers. During the same period, we find the first ‘stars’ of the era, female singers and ‘castrato’ singers who became famous for their success on stage.

Opera, during this long and yet very short period of time since its theoretical conception, evolved from a pastoral drama accompanied by simple music to a musical spectacle of highly technological stagecraft, with a devoted audience and the first ‘stars’ of the music scene. Monteverdi influenced the development of opera so fundamentally that his first and last works reflect the entire development of the genre. From L’Orfeo of 1607, a musical drama with a mythological theme, whose audience was exclusively members of the aristocracy, to the opera L’incoronazione di Poppea of 1643, with a historical theme, which was performed in a commercial theatre in Venice, open to a wider range of social classes.9Taruskin, R. (Ed.) 2010. The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 2, ‘Music in the 17th and 18th centuries’, p. 6 The theories of Camerata and the creators, who were inspired by this musical-theatrical genre, combined cultural influences, popular ideas of their time and old and new musical ideas to create a new kind of entertainment on stage. As is often the case in both the arts and the sciences, these ideas became a thing of their own and created an exciting new artistic universe full of music.

Let us now look at a short extract from an opera composed by the English composer Henry Purcell fifty years after Claudio Monteverdi’s death.

Excerpt from the Greek National Opera’s production of The Fairy-Queen by Henry Purcell. Conductor: Markellos Chryssicos, stage direction: Giannis Skourletis / bijoux de kant (2018)

QUIZ / THE BIRTH OF OPERA

ACTIVITIES / THE BIRTH OF OPERA

Introduction

“A Camerata in our own classroom”

Connection to the curriculum

– Ancient Greek texts in translation

– Music

Main themes

– Ancient Greek Homeric epic poems

– Florence, 16th century (Camerata)

– Libretto

Suggested duration

2 teaching hours

Educational objectives

– Connection of ancient Greek texts with contemporary themes

– Development of critical thinking

– Development of communication and rhetorical skills

– Development of creativity

– Promotion of collaborative practices (in the classroom)

As we saw in the section “The birth of opera”, the Camerata was a group of noblemen and musicians who began to discuss the relationship between rhetoric, music and science in the second half of the 16th century in Florence, in present-day Italy. The aim of Camerata was to revive ancient Greek drama, which had survived only in written descriptions. Through the debates and experiments of this group, the musical drama, precursor of the genre of opera, was born.

In this activity we will try to create a slightly different contemporary Camerata in our classroom. Our classroom will be transformed into Camerata and we, as a group of noblemen and musicians, will engage in the process of studying excerpts from Euripides’ Helen. We will share ideas about the work that can serve as a starting point for a new opera, which will draw inspiration from the past and connect with the present.

Step 1

Read carefully the following excerpts from Euripides’ Helen.

Euripides’ Helen -> FIRST STASIMON

(Lines 1151-1164)

You are fools, who try to win a reputation for virtue through war and marshalled lines of spears, senselessly putting an end to mortal troubles; [1155] for if a bloody quarrel is to decide it, strife will never leave off in the towns of men; by it they won as their lot bed-chambers of Priam’s earth, when they could have set right by discussion [1160] the strife over you, O Helen. And now they are below in Hades’ keeping, and fire has darted onto the walls like the bolt of Zeus, and you are bringing woe on woe.

translated by E. P. Coleridge

Euripides’ Helen -> SECOND STASIMON

(Lines 1353-1368)

You made burnt offerings that were neither right nor holy, in the chambers of the gods, [1355] and you have incurred the wrath of the great mother, child, by not honoring her sacrifices. Oh! Great is the power of dappled fawn-skin robes, [1360] and green ivy that crowns a sacred thyrsos, the whirling beat of the tambourine circling in the air, hair streaming wildly for the revelry of Bromios, [1365] and the night-long festivals of the goddess. . . . You gloried in your beauty alone.

translated by E. P. Coleridge

Step 2

After you have finished reading, choose one of the texts.

Τhe excerpt from Stasimon Α’ (Β’ antistrophe, lyrics 1270 – 1285), is a pacifist statement expressed through the Chorus. The Chorus emphasizes the absurdity of war and proposes words, as opposed to weapons, for conflict resolution.

In the excerpt of Stasimon Β’ (Β’ antistrophe, lyrics 1483 – 1499), the Chorus addresses Helen, speaking of “what she shouldn’t have touched”, referring to her excessive beauty (lyric 1498). As you will notice, here as well we are confronted with the issue of Helen’s guilt and her powerlessness against her nature and her beauty.

As a new Camerata, which of the two themes would you like to highlight?

Step 3

Read the text a second time and discuss the following questions, with the help of your teacher:

1. Is your excerpt still relevant today and why?

2. Which contemporary events can you associate this excerpt with?

3. Think of a contemporary event that is related to the theme of your excerpt and would be worthy material for writing a new opera.

4. Think of a title for this performance of the “new Camerata“. Write a short paragraph summarizing the main idea of the performance.